The Circulating Tumor Cell Challenge

August 2, 2019

Illustration by Brian Stauffer

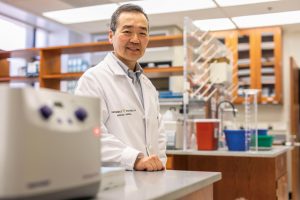

Medical oncologist and cancer geneticist Ben Ho Park, MD, PhD, has set his sights on a new era of breast cancer patient assessment, which, in turn, could usher in a new level of precision treatment.

“I want to figure out whether liquid biopsy is as good as we think it is. Can we use it in the future to say, ‘You’re cured?’” Park said.

Liquid biopsy refers to testing of blood or other body fluid for disease detection, diagnosis and prognosis. In cancer, liquid biopsy has become a particularly thriving area of research with potential to revolutionize patient assessment. Because it’s much less invasive than tissue testing, liquid biopsy could prove far more agile in clinical decision-making.

Park’s work on liquid biopsy is a natural extension of his consequential and ongoing research in breast cancer genetics and precision drug therapy. Ben Ho Park is the Donna S. Hall Professor of Breast Cancer and professor of Medicine at Vanderbilt University and co-leader of the Breast Cancer Research Program, director of Precision Oncology and associate director for Translational Research at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. Also, Park helps advise the nation’s leading breast cancer organization, Susan G. Komen (formerly known as Susan G. Komen for the Cure), as one of 59 Komen Scholars.

Immune to hype

Much of the talk around liquid biopsy concerns prospects for an annual routine screen for ultra-early-stage cancers of all types. Ticking off some of the major unanswered questions hanging over this prospect, Park admits to some doubts. “I don’t know that I’ll actually still be alive by the time we figure that one out,” he said.

Concerned with more immediate prospects, Park appears immune to the hype that has grown up around liquid biopsy, and he casts a critical eye on much of the published research. His sober views seem to reflect a steely-eyed determination to carry this challenging line of research through to application in the clinic.

He puts the stakes for breast cancer patients in stark terms.

“We’re essentially obligated to overtreat early-stage breast cancer, which I’ve always seen as one of our biggest unresolved issues,” Park said. “After their surgery, we know that around 70% of these patients will be cured, but without additional therapy the remaining 30% will recur with metastatic disease within 20 years. Because typically we have no way of distinguishing these two groups, on top of surgery almost everyone gets chemotherapy and perhaps additional therapies.”

While these adjuvant therapies reduce rates of metastatic recurrence by half or more, saving thousands of lives each year, they also pose common unpleasant side effects and, for some patients, more serious risks.

In cases that call for pre-surgical chemotherapy, trials relying on the test of time have shown this is often curative, but again there’s currently no way of predicting who still needs the surgery and who doesn’t. “It took me a long time to convince people that liquid biopsy might help here,” Park said.

Today, if there were a way to distinguish patients who aren’t responding to standard chemotherapy, “you could make the argument those patients need to go on a clinical trial ASAP with newer agents,” Park said. Because liquid biopsy results are both quantitative and qualitative, they could also be used to guide precision drug therapies.

Finally, there are 3.1 million women with a history of breast cancer in the U.S. “There are so many patients who live in fear every day because they don’t know if they’re cured or not,” Park said.

Ben Ho Park, MD, PhD, has a new multicenter clinical trial to help decide the utility of liquid biopsy for clinical decision-making in breast cancer. Photo by Anne Rayner.

Speaking in his office high in the Preston Research Building at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Park takes pains to highlight reasons for caution concerning liquid biopsy.

“A lot of people are quick to use these tests, and sometimes I think inappropriately, just out of ignorance. On this I always quote Dan Hayes, one of the godfathers in the field of biomarker development, who says a bad test can be just as dangerous as a bad drug. If we really want to do good for our patients, we need to put biomarkers to the same rigor that we use in drug development and prove that not only does the test work for detection, but it actually leads to something clinically actionable. Many biomarkers have been proven to show things, but very few have graduated to the next step that actually affect outcome,” he said.

To help decide the utility of liquid biopsy for clinical decision-making in breast cancer, Park has a new multicenter clinical trial underway. Some 228 patients will receive both tissue testing and liquid biopsy before pre-surgical chemo, before surgery, after surgery and as post-surgical treatment is continued.

Where’s Waldo?

Where injury or infection is involved, cell death can be premature and messy, but normal cell death is programmed and orderly, at rates in the billions of cells per hour (with lifespans varying wildly across different cell types). Castoff cellular material is recycled by the immune system, but crumbs find their way everywhere, including DNA fragments that wind up briefly in the bloodstream before elimination by the kidneys and liver. Circulating cell-free DNA, or cfDNA, was first identified in 1948.

Cancer is a genetic disease, with tumor cells hosting genetic mutations not found in normal cells. Early methods of DNA analysis weren’t conducive to the task of distinguishing circulating tumor DNA, or ctDNA, from normal cfDNA fragments in blood plasma.

“Are you familiar with Where’s Waldo?” Park asks.

To illustrate the technical challenge, Park turns to images from a well-known children’s book series that features double-spread, colorful bird’s eye drawings of jumbled crowds of people. The reader’s goal is to spot Waldo, a lanky figure in a red-and-white striped sweater and round glasses; adding to the fun, red-and-white herrings are placed throughout the drawings.

In Park’s analogy, a given Where’s Waldo? drawing represents a blood plasma sample hypothetical assay; each person in the drawing represents a cfDNA fragment in the plasma sample; any red-and-white striped object represents a DNA fragment of interest, that is one that coincides with DNA known to host the mutation of interest in the assay; finally, Waldo represents the mutation. Finding “Waldo” is difficult.

A 1999 study introduced a method called digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which allows quantification of specific cancer tumor DNA mutations in blood plasma. Delays associated with conventional tissue testing emerged as a snag in clinical trial design for a targeted breast cancer drug that Park was studying during his early faculty years at Johns Hopkins. This drew his attention to digital PCR as a potential alternative. His first venture in this area was a proof-of-principle study comparing concurrent tissue findings and liquid biopsy findings from the same metastatic breast cancer patients.

“It turned out that the new method was pretty darn good. That was to my knowledge the first study showing that you could do liquid biopsy, as it’s known today, in a reliable fashion for metastatic breast cancer,” he said.

Digital PCR is no longer the only option for cancer liquid biopsy.

“The various technologies have fancy names, but what they all do is take the sea of DNA in a plasma sample and separate out each individual DNA fragment rapidly, then massively in parallel, sequence each of those strands,” Park said.

The sequencing occurs in arrays of tiny test wells. In a cancer assay, any well containing the mutation of interest turns brightly fluorescent. In relation to a given locus in an individual’s 3-billion-letter DNA sequence, liquid biopsy quantifies the proportion of mutated and normal DNA fragments in a blood plasma sample.

The proportion can be very low. “There’s really no lower limit of detection, it’s only a matter of how many molecules of DNA you can pragmatically assay, time-wise and money-wise,” Park said, adding that his lab has been using one in 10,000, or 0.01%, as a cancer detection threshold.

“I am trying to focus on what I think I can get done in the next five to 10 years. This new study is the first multi-institutional study looking at the cell-free DNA question, and the most important outcome will be whether a positive blood test predicts cancer recurrence and does a negative test predict a cure. It’s going to be another five to 10 years before that information is complete,” Park said. “This trial took us forever to get up and going, but we finally did. It’s completed patient accrual. We are now collecting the samples, and we’re waiting.”