Cracking the Colon Cancer Conundrum

Researchers reflect on 20 years of successes

November 7, 2022

Twenty years ago, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) established the nation’s first Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) to focus exclusively on colorectal cancer, the second leading cancer killer after lung cancer. Directed by Robert J. Coffey, MD, and continuously funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) since 2002, the gastrointestinal (GI) SPORE has fostered a highly productive research enterprise that has led to breakthroughs in understanding how colorectal cancer develops, and which has identified new avenues for early diagnosis, treatment and prevention.

VICC had two major strengths in 2002 that positioned it to win the highly competitive initial grant:

• A deep bench in basic science, overseen by Coffey, which among other areas was defining the pivotal role that the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and its ligands, the signaling proteins that bind to it, play in the development of colorectal cancer; and

• An equally strong phase 1 clinical trial program, directed by Mace Rothenberg, MD, whose contributions to the development and eventual licensing of several cancer chemotherapy drugs were legendary, and who would serve as the SPORE’s co-director.

Both men held faculty positions in the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine as professors of Medicine and endowed Ingram Professors of Cancer Research. But their ambitious program nearly didn’t get off the ground.

By the time Coffey heard about the opportunity to apply for a GI SPORE grant in January 2002, the submission deadline was just six weeks away. “This was back in the day when there were paper submissions,” he said, “and these grants would get up to 800 pages.”

Coffey recalls going two to three days without sleep, catnapping on the floor of the local Kinko’s while copy machines churned out multiple copies of the application.

“We were scrambling, but when something needed to be done, people delivered,” recalled Rothenberg, currently a member of the VICC Board of Overseers who recently returned to Nashville after a 12-year career at the pharmaceutical giant, Pfizer.

“That’s one of the real defining characteristics of Vanderbilt,” he said. “It’s an extraordinarily collaborative institution. That’s what has made Vanderbilt so successful over the years.”

The lesson was that cancer was not a straight line of interactions involving the EGF receptor, as the researchers had expected. “Even from cancer to cancer, the role of the receptor could be different,” Rothenberg said.

Robert Coffey, MD, left, and Mace Rothenberg, MD, in 2007, after receiving GI SPORE funding renewal from the National Cancer

Institute.

Mere hours before the submission deadline in March 2002, Coffey was rushing to the airport with the courier he’d hired to hand-deliver the completed application to the NCI outside Washington, D.C., when he was pulled over for speeding on West End Avenue.

“I was looking pretty disheveled,” Coffey admitted, but the officer accepted his urgent tale, waved them on, and the courier made his flight.

The initial grant, which provided $13 million over five years, supported five projects. Among them was a clinical trial of the investigational EGFR blocker gefitinib (Iressa) in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Directed by Rothenberg and conducted through the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, the trial accrued more than 100 patients and was the first to analyze the biological effect of the drug in biopsies of patients’ tumors.

Iressa had been approved to treat non-small cell lung cancer. But in the colorectal cancer trial, the drug showed a biological effect, but failed to slow tumor growth.

Despite this early setback, the Iressa trial led to another, ultimately successful approach — using monoclonal antibodies to block the EGF receptor. “Sometimes even failed experiments, from a clinical perspective, can give us insights that help direct us into more promising and fruitful directions,” he added.

High risk, high payoff

Meanwhile, the researchers were pursuing other leads. As Coffey is fond of repeating, “we decided to ‘roll the dice’ and propose high-risk, high-payoff projects.”

Those projects included studying polarized colorectal cancer cells in vitro to understand how they compartmentalize and traffic EGFR and its ligands, and then testing newly gained insights in mouse models and clinical trials.

Another novel approach led by Daniel Beauchamp, MD, at the time chair of the Section of Surgical Sciences, was the high-throughput screening of libraries of synthetic small molecules and natural products to identify agents that could block pathways of signaling proteins that were implicated in the development of colorectal cancer.

These efforts, many of them facilitated through the Epithelial Biology Center, which Coffey established in 2010, helped upend the long-held assumption that cancer results primarily from genetic mutations. On the contrary, “epigenetic” factors that influence the activity and behavior of normally functioning genes and cells also can promote tumor growth.

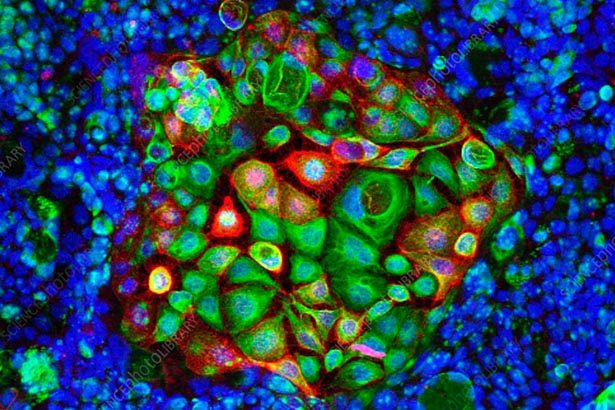

Epithelial cells that form the interior colon lining, mesenchymal cells, which develop into connective tissues and blood vessels, inflammatory cells, and tumor-initiating cells (also called cancer stem cells) — all these and more play a role in cancer. “It’s almost like a conspiracy,” Rothenberg said.

Cells, including cancerous ones, can communicate with each other by sending protein and RNA messages packaged in extracellular vesicles called exosomes. Last year the Coffey lab identified another extracellular mode of communication, via nanoparticles they dubbed “supermeres.”

Outside agitators — bacteria — also may play a role. In June, researchers from VICC and Johns Hopkins reported that a toxin-producing strain of the bacterium Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) drives tumorigenic changes in the colon in mice.

Patient advocacy

Understanding what’s going on at the molecular and cellular levels is vital to cracking the cancer conundrum. But at the same time, the researchers never let their attention stray from the patients who stood at the center of their mission.

From the beginning, efforts were undertaken to identify markers that help monitor the response to chemotherapy and radiation, and which could detect early recurrence of colon polyps. The goal was to identify which patients might benefit most from regular screenings and preventive treatment.

VICC’s GI SPORE also was among the first in the country to assign cancer survivors and family members to each project as patient advocate members of its advisory board “to make sure what we’re doing has relevance to patients,” Rothenberg said.

Ron Obenauf is a colorectal cancer survivor and retired businessman from Shelbyville, Tennessee, who has served as a patient advocate since 2005.

Advocacy is a way for grateful patients to give back, said Obenauf, who has also helped support the research financially. “We’re there to put a face on cancer,” he said, “and to give the patient’s perspective. What is the goal here? How soon are we going to get some benefit?”

Those are the same questions Rothenberg has asked throughout his career. They are one reason he left VUMC in 2008 to join Pfizer as a senior vice president and chief development officer for oncology, and subsequently as the company’s chief medical officer.

Academic medicine, industry and the government are part of an “ecosystem,” Rothenberg said. “One can’t reach its full potential without the other. You can have the most elegant scientific discovery in the world, and without it being translated into detection or prevention or treatment, you can’t help a single patient.”

Targeting pathways

Recent advances from the VICC’s GI SPORE include identification of potentially targetable elements of cancer-promoting signaling pathways, including WNT, KRAS, MYC — and EGFR.

WNT proteins normally regulate the formation of tissues and organs during embryonic development. In the colon, defective WNT signaling in inflammatory, epithelial, mesenchymal and stem cells can contribute to cancerous growth in different ways.

KRAS is a small, ball-like protein that normally serves as an on-off switch, regulating cell growth. When the KRAS gene is mutated, the protein can become stuck in the “on” position. MYC is a chromosome-binding protein that regulates thousands of genes involved in growth and duplication, and which has also been implicated in cancer.

In the colon epithelium, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) regulates the immune/inflammatory response to infection, and normally suppresses tumor growth. The Beauchamp lab has found that loss of the TGF-beta signaling protein SMAD4 results in

increased expression of inflammatory genes, and increased susceptibility to inflammation-driven carcinogenesis.

Targeting each of these pathways could lead to new cancer treatments. For example, in 2018 a team led by Coffey and Ken Lau, PhD, identified a transmembrane protein called LRIG1 that, by antagonizing EGFR signaling, acts as a tumor suppressor.

More recently, Stephen Fesik, PhD, William Tansey, PhD, and their colleagues solved the crystal structures of MYC proteins, revealing crevices to which specially designed small molecules can bind and potentially block the protein’s action.

It’s an example, Rothenberg said, of a research program initiated through the GI SPORE that has garnered additional NCI funding.

“We’ve been given $200,000 a year for the MYC project,” added Coffey, who is preparing to apply for the fifth renewal of the GI SPORE grant this fall. “With a relatively small investment, we’ve made enormous progress.”

There is still much to learn. While the death rate has declined significantly during the past 20 years, colorectal cancer remains the nation’s second leading cancer killer — and is expected to claim more than 52,000 lives this year.

Cancer research is an often humbling experience. “We’re never as smart as we think we are,” Rothenberg said.

That’s why collaborative, comprehensive research efforts like VICC’s GI SPORE are so important, he said. The challenge going forward is to put all the puzzle pieces together.