A silly song

Survivor finds humor in diagnosis with rare disease

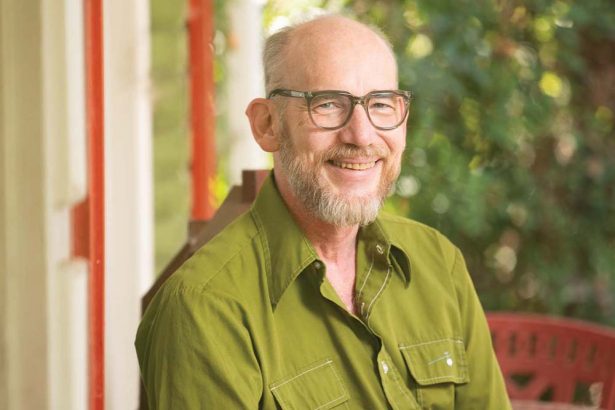

November 30, 2023 | John Delworth

Try to sing this to the tune of “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious:”

Auto-immune slash cancer disease

With a half-decent prognosis

Plays hell with my skin and

Gave to me a brain tumor atrocious

At least of all these nasty things

I don’t have halitosis

I have got the Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis!

Um-dittle-ittl I’m not gonna die

Um-dittle-ittl I’m not gonna die

LCH is my rare disease. It ain’t so bad, but only because it was discovered early. Here’s how my story goes.

I went to a sub shop for lunch on July 6, 2018, bit into the sandwich and immediately felt this weird tingling across my face. I thought I had a reaction to one of the ingredients and waited to see if it would go away, but the tingling refused to leave me alone.

A few days later, I saw my regular doctor, Robert Crowder, with Heritage Medical in Nashville. Because it sounded like a nerve thing, and nerve things are usually on one side of the body or the other, it concerned him that this was on both sides of my face. He scheduled me for a brain MRI the next day and called me a couple of hours after the scan with the results. He phrased the news the same way I would phrase it when telling family, friends and co-workers. It seemed like the perfect way to convey the news and put them at ease at the same time. Like when day care calls you at work, the first thing out of their mouth is that your kid is OK, but…

Dr. Crowder had two sentences for me: “It’s probably not fatal, but you have a tumor on the pons of your brain stem. Because of its location, it can’t be surgically removed, so they will probably use radiation.”

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis is rare. It’s like cancer, but it isn’t. It acts like an autoimmune disease, but it isn’t. My body makes too many immature Langerhans cells called histiocytes that form tumors or damage organs, bone or tissue.

Apparently, biting into the sandwich just happened to coincide with the moment my tumor grew large enough to push on the big nerve coming out of my brain before it split into the right and left parts of my body. I spent the summer tingle-faced while they searched the rest of my body for clues (thus discovering I have LCH) until they zapped it with radiation and killed it dead in the fall. But the tumor was only the first of our discoveries.

I was alone at the house when I had gotten that call from the doctor. I felt dread for sure. I pondered death, of course, but I really dreaded telling my wife, Dana, and our two teenagers. Dana was out having dinner with friends at the time. Knowing she didn’t drive there, I hatched a plan. I texted her that I would join her and give her a lift home. I figured that telling her in the car while I was driving us home would be the soonest I could break it to her alone and in person. I practiced the two sentences on the way there and sat at the outdoor table with everyone for an hour, laughing it up and enjoying the sight of her being blissfully unaware.

I carried out the plan, and she was naturally devastated. It went the same with the kids. It never got easy to break the news to people. Saying it out loud remained uncomfortable.

Doctor visits followed. My fantastic wife took control of information, like remembering all the things I forgot to tell them and asking all the questions we needed answered. She started a journal to keep track of all the details and brought it to every visit.

Dr. Crowder first prescribed a daily steroid to shrink the swelling around the tumor, which reduced the tingling from a constant buzzzzzzz to a low yet constant purrrrrr. The tumor board at Nashville’s Saint Thomas Hospital West discussed my case on Thursdays and, over the following months, ordered up MRIs, PET scans, CT scans, more types of scans and a lung biopsy. My wife added a zipper bag to keep the journal, full-color photos and CD copies of all the scans.

The big question they sought to answer was whether my tumor was benign. Answers to our questions were hard to come by during the weeks between lab visits and consultations. It was agonizing and made us feel like members of the national guard of Kafka-stan: caught in some existentialist quagmire, always ready for the next call, never sure what was next. Eventually, a nurse practitioner friend noticed in my wife’s posts on social media that we were having difficulty getting answers. As it turned out, this friend was on the tumor board at Saint Thomas! She answered our questions and was the one on the board who came up with the Langerhans diagnosis. The subsequent CT chest scan showed the telltale cysts in the lungs, and a lung biopsy confirmed it. No signs of cancer were detected anywhere in my body, and the tumor had not grown since first detected. Conclusion: brain tumor benign. Whew!

I felt doubly blessed because all the poking and prodding assured this 52-year-old that I had no other lurking widow-makers. I will also benefit from insurance-paid scans going forward. Who else gets to say that?

Um-dittle-ittl I’m not gonna die

Um-dittle-ittl I’m not gonna die

Months of daily steroids took their toll. Carbonated beverages tasted terrible. I could only sleep for a few hours each night. My feet were heavy. As fall began, the tumor was zapped by radiation, and I took home the radiation mask and decorated it as many survivors do. It’s made of hard plastic mesh that was molded to the shape of my head and used to bolt my head to the table so I wouldn’t move while protons were beamed into my brain. This was extremely important because the zapping, as calculated by the brilliant Dr. Paul Rosenblatt, had to go to the exact place where the tumor was without damaging any other part of my brain, like where I store the instructions on how to ride a bike or who shot J.R. I went to the Dan Rudy Cancer Center at Saint Thomas every weekday morning before going to work in October of 2018 and walked away with a dead tumor, a face that no longer purred and the knowledge that it was Kristin who shot J.R.

Survivors often make art out of their radiation masks. I made mine into a KerPlunk-style game with colored sticks stuck through the holes of the mesh that hold up dozens of blue-colored balls and one white ball that represented the tumor. “Fun for the whole family, the object of the game is to remove the tumor without losing all your marbles!”

In my case, living with LCH means I will take handfuls of pills for the rest of my life, or as I phrase it, “All I have to do is take handfuls of pills, and I get to lead a normal life.” Each pill represents a problem that popped up and had to be smacked down like we were playing Whac-A-Mole. These include one pill for my thyroid that turned crispy and had to go, one pill for the kidney function-enabling hormone no longer made by my pituitary gland, three pills to calm down my liver enzymes, and I take vitamin D for a reason I keep forgetting. Another hormone my pituitary gland stopped making, testosterone, is now provided by a gel I rub over my shoulders every morning because the alternative is giving myself shots.

Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center has an expert on staff for this rare disease, Dr. Sanjay Mohan, who oversees my issues and shares advice on the latest bingeworthy TV shows, which we reciprocate. He gets bonus points for having attended one of my band’s late ’90s D.C.-area shows.

In 2022, Langerhans got bored and started messing with my skin, statistically one of its favorite pastimes. Langerhans saw my outer ear canals as nice places to cause lesions that would not heal. We added an ear, nose and throat doctor to my stable of experts, and he surgically removed the lesions three times. The fourth time this ear thing came back also coincided with a gaping dime-sized sore in my armpit that refused to heal. That one hit close to the lymph nodes, and Dr. Mohan decided it was time to start chemotherapy and put this disease into remission. No more pumping quarters into the Whac-A-Mole machine — it’s time to turn it all the way off.

I am finishing up a yearlong, moderate-dose chemotherapy regimen of cytarabine we started in October of 2022. I go to the infusion clinic at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center for one week each month. The side effects are few and mild. My wife and I get a private room with loungers and a TV. They bring us heated blankets, snacks and drinks. Unlike many chemo patients who make long commutes that upend their and their loved ones’ lives, I live here in hospital-abundant Nashville. My workplace is a six-minute drive from the Cancer Center, and with each visit only lasting a couple of hours, I’m not even missing work. I usually have my laptop computer with me, even joining Zoom meetings while hooked up. The major skin issues have cleared up; all that remains is a round of body scans to double-check.

From now on, I will rely on and look forward to regular visits with Drs. Crowder and Mohan, endocrinologist Dr. Craig Wierum, gastroenterologist Dr. David McMillen, and my ear nose and throat guy Dr. Greg Mowery. I wouldn’t be in this comfortable and peaceful place without them.

My entire body is behaving better, and to keep it that way, I will keep taking my handfuls of pills. Another indication the chemo worked is that since I started, the only pills I’ve added are calcium supplements because I have the bone density of a 70-year-old (thanks, Langerhans). Here’s hoping that’s the last mole to be whacked.