Homestyle Care

Vanderbilt-Ingram devises CAR T treatment protocol without hospital stay

April 26, 2023

When the first cancer patients in Tennessee underwent chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in 2015, they had to be hospitalized for two months and closely monitored for serious reactions. Those clinical trials by oncologists at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and other academic centers nationwide led to the approval of the powerful new immunotherapy for patients with large B-cell lymphoma that had stopped responding to conventional treatment. Now, Vanderbilt oncologists have demonstrated that patients can receive the treatment liberated from a hospital room.

The outpatient protocol they developed has gained national attention and will soon be emulated by other cancer centers.

“We have taken the bull by the horns,” said Olalekan Oluwole, MBBS, MPH, associate professor of Medicine. “We carefully selected patients and wrote up a detailed protocol to treat them outpatient if they met specific criteria, and then we refined that protocol to keep as many as we were able to be safely treated in an outpatient setting.”

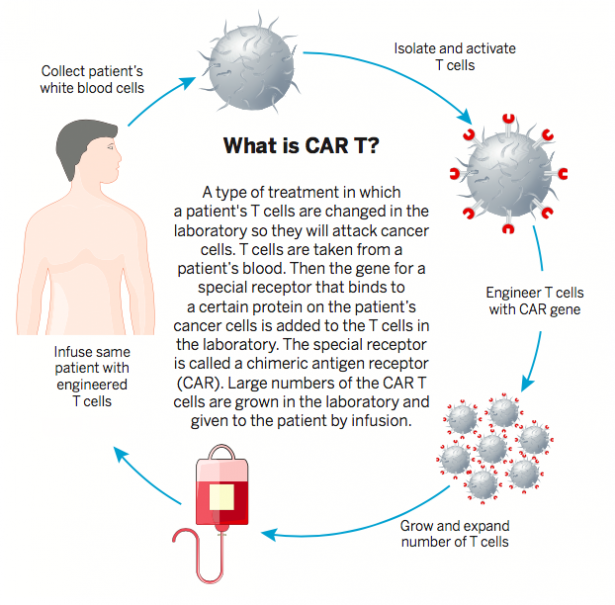

CAR T immunotherapy reengineers patients’ T cells to recognize and kill cancer cells. The Food and Drug Administration has in recent years expanded approvals of CAR T therapies for more cancers, including other types of lymphoma, multiple myeloma and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Since the therapies supercharge patients’ immune systems, serious complications can occur, including dangerously high fevers, steep drops in blood pressure and organ failure.

However, confining CAR T patients in hospital rooms for such a long period was bad for their morale, an additional treatment expense, and utilized hospital beds needed by other patients. The Vanderbilt-Ingram outpatient protocol requires patients to stay within 30 miles of Vanderbilt University Medical Center. They are also closely monitored via telemedicine technology after they receive their CAR T infusion.

Shannon Findley of Knoxville, Tennessee, and her husband, Patrick, set up temporary residence in Nashville to receive this new CAR T treatment after she had previously received multiple types of chemotherapy for her large B-cell lymphoma that didn’t have a lasting response. Instead of being confined to a hospital room, she was able to take walks around the Parthenon at Centennial Park and tour museums.

“It is nice to be able to be out in the world, to see people,” she said. “We would go on mini road trips in and around Nashville, and we would forget about the cancer for a little bit.”

Telemedicine Monitoring

That didn’t mean Findley was forgotten by her care team at Vanderbilt-Ingram. Her temperature, blood pressure and oxygen levels were continuously tracked through a monitor she wore. She also had a morning clinic appointment each day and then a remote telemedicine visit each evening with a nurse practitioner who checked for any nervous system problems, such as confusion or tremors.

“One day, Patrick and I were at the grocery store, and I was sitting in the car in the sunshine,” she said. “The heat was on me. My nurse, Nancy, called me and asked, ‘Are you OK? Your temperature is 100.5.’ I told her I was sitting the sunshine, and she said, ‘We will keep an eye on you.’ By the time I got back to the apartment, my temperature was still going up. She said, ‘You need to come to the hospital now.’”

Fever is a common side effect with CAR T therapy, which can be effectively treated, but it may be an early symptom of cytokine release syndrome (CRS), an over-response by the immune system that can lead to more serious complications. Findley’s care team took actions to lower her temperature, and she avoided the inflammation of vital organs that occurs with a serious CRS reaction.

The potential benefits from CAR T therapy outweigh the possibility of complications from the treatment for people like Findley. The immunotherapy offers a second chance for patients with certain blood cancers who have stopped responding to conventional treatments or who have relapsed after those treatments.

Personalized Medicine

CAR T is customized for each individual patient. First, a patient’s blood is collected, and their white blood cells, which include the T cells, are isolated during a process called leukapheresis. The patient’s frozen cells are then sent to a specialized lab where chimeric antigen receptor gene constructs are engineered into the T cells and multiplied. Meanwhile, the patient undergoes low-dose chemotherapy to decrease their T cell level and make room for the CAR T cells to grow after receiving them in an infusion clinic. The infusion is administered just once in most cases.

Findley, a former legal secretary with three children and six grandchildren, had been enjoying retirement for about two years when she was diagnosed with cancer. It didn’t seem real when she heard the initial report from her CT (computed tomography) scan after seeing a urologist for a urinary tract infection.

“When the doctor was talking to me, she kept saying, ‘I need to refer you to oncology,’ but I was hearing urology. I said, ‘You are the urologist.’ It was a big surprise. Luckily, my husband was with me,” Findley recalled.

A biopsy confirmed that she had follicular lymphoma. She first underwent one round of chemotherapy in February 2021, followed by a stronger regimen of chemotherapy. In June 2021 she rang the bell at the cancer center in Knoxville where she had been treated to celebrate the completion of the chemotherapy.

But a subsequent PET (positron emission tomography) scan indicated cancer.

“That’s when they found two hot spots, and that’s when they recommended for me to go to Vanderbilt, which was a blessing,” Findley said. “You can tell that my doctors and nurses and caregivers want to be there. They are all kind, even the people in the cafeteria. They made it all easy.”

In January of 2022, she and her husband relocated to a Nashville apartment for seven weeks for her to undergo CAR T therapy and be monitored. So far, her lab reports have been good. One of the tumors no longer shows up on scans, and the other has decreased.

Findley is back to enjoying her retirement, taking long walks in her neighborhood, attending festivals, spending time with grandchildren and painting for pleasure.

Charlotte Tacon of Huntsville, Alabama, has also received CAR T therapy on an outpatient basis. She lived with her daughter in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, during April and May of 2022 while being monitored.

She underwent a PET scan in Huntsville the day before Thanksgiving in 2020, then learned a week later she had large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It had spread to her bones and lymph nodes. She finished chemotherapy in May of 2021. Initially she thought she was cancer free after chemotherapy, but then in the middle of a September night that year, she experienced stomach pain so excruciating that she went to an emergency room. The next morning, she learned her cancer had come back.

Her oncologist in Huntsville suggested CAR T therapy and referred her to Vanderbilt-Ingram.

“I said, ‘Sure. Why not?’ I didn’t know much about it,” Tacon recalled. “I did read about Dr. O, and I saw that he had lots of credentials.”

CAR T Expertise

Oluwole’s patients often call him “Dr. O,” and he is one of the nation’s top CAR T experts. He is an author of a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2017 that showed CAR T is an effective treatment for refractory large B-cell lymphoma.

“I have been home since mid-May, and I’ve been doing really well,” Tacon said. “I run into friends, and they say, ‘Gosh, you look so much better than the last time I saw you. You’ve got color back. You’re gaining weight.’ My CAR T cells are fighting and killing the cancer cells that they can find.”

Tacon is in remission. She spends her time taking care of Zorro, her 12-year-old cat, and doing plastic canvas knitting.

Oluwole said it was imperative, for several reasons, that a better way for monitoring CAR T patients be implemented.

“Cost is one factor, but it was really not the major driver,” he said. “The major driver — believe it or not — was the diminished patient comfort with extended hospital stay.”

Oluwole, who is also an expert on stem cell transplants, and his colleagues built upon the foundations of Vanderbilt’s highly respected outpatient program for stem cell transplant patients. The Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Stem Cell Transplant program consistently ranks among the best in the nation for donor stem cell transplant survival rates among large centers.

“This is a project that we have built from the backbone of what we had already done successfully, which is allogenic (donor to patient) stem cell transplants in the outpatient setting,” he said. “There are some similarities between CAR T and stem transplants. Of course, there are also differences. We had multiple meetings and troubleshooting sessions for how we could make this a safe transition. There are several CAR T products. Some of them don’t have as many side effects as others, but it turns out that the one that has the highest response rate also has the higher rates of cytokine release syndrome. It was quite challenging, but we successfully transitioned our CAR T program to the outpatient setting.”

Another factor was the need for more hospital beds because of the COVID pandemic, he said. As a major tertiary care center, VUMC already had high demand for hospital beds before the pandemic.

Oluwole is the principal investigator of a study to gauge how well the outpatient program for CAR T patients works. A larger clinical study is in the works that will be based on the data from Vanderbilt.

“We are leading this initiative nationally, to do the CAR T treatment completely outpatient,” he said. “The telemedicine portion is very, very user friendly. The patients love it. It takes a few clicks through the My Health at Vanderbilt web portal. It’s been very good for patients.”