The Cancer Sleuth

Bill Blot made Vanderbilt an epidemiology powerhouse

September 30, 2021 | Bill Snyder

Photograph by Ken McCray

William J. “Bill” Blot, PhD, was already a well-known cancer epidemiologist — one who tracks the incidence and distribution of malignancies and factors that cause them — when he agreed to help Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) grow its own epidemiology program in 1999.

His move to Nashville was pivotal, for here, in collaboration with Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) and historically black Meharry Medical College, Blot and his colleagues launched the first major study to find out why Blacks in the southern United States have such disproportionately high cancer rates.

Twenty-two years later, the Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS) is the gold standard for research aimed at uncovering the myriad factors — environmental, genomic and socio-demographic — that affect not only the burden of cancer in underserved and underrepresented populations, but also many other diseases.

For Blot, 77, who retired from the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine faculty this spring, the SCCS is the capstone of a 50-year-long career that, according to his admirers, has had a profound effect on advancing the control and prevention of disease.

Blot “ranks among the most accomplished cancer epidemiologists in this country,” says Wei Zheng, MD, PhD, MPH, Anne Potter Wilson Professor of Medicine and chief of Epidemiology at VUMC. “His contribution in this area has enormous impacts in reducing cancer incidence and mortality in the U.S. and around the world.”

The SCCS remains an important resource for uncovering molecular mechanisms of cancer and for developing strategies to address cancer health disparities, adds Samuel Adunyah, PhD, chair of the Department of Biochemistry, Cancer Biology, Neuroscience and Pharmacology at Meharry. “Without Dr. Bill Blot’s leadership and input, the SCCS would not have been possible,” he says.

“A lot of things fell in place,” Blot responds with characteristic modesty. The National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health, funded the cohort study because “people realized this needs to be done. It’s a real team effort,” he said.

“He is very modest,” agrees Harold “Hal” Moses, MD, founding director of the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and professor of Cancer Biology, emeritus. But “in some ways that’s misleading because he’s a real leader. Bill Blot has done an absolutely phenomenal job in bringing us to where we are now.

“Now Vanderbilt is a powerhouse of cancer epidemiology,” Moses says, “and it goes beyond cancer.”

Breath of Fresh Air

A native of New York City, Blot finished high school and college in Florida, earning a PhD in statistics from Florida State University in Tallahassee in 1970.

“My very first job after graduating was in Hiroshima, Japan,” Blot says. “I was working for what was then the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission.” Among his published studies from that time: the impact of radiation exposure on fertility rates and on the physical and mental development of children.

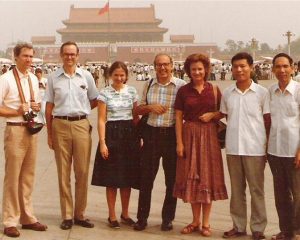

Bill Blot, PhD (pictured far left), visited China early in his career with colleagues from the National Cancer Institute to promote an international collaboration to better understand the causes of cancer. Submitted photo from National Cancer Institute.

In 1974 Blot began a 20-year stint at NCI, the last 10 as chief of the Biostatistics Branch. There, he led a program of epidemiologic and biostatistical research that included mapping the nationwide distribution of cancer mortality and investigating often-marked disparities in cancer incidence and death rates between different population groups.

He also helped initiate several cancer epidemiology studies in China, Italy and other areas of the world where distinctive cancer patterns provided clues to etiology, or factors that spur malignant growth.

Blot left NCI in 1994 to cofound the International Epidemiology Institute (IEI), a biomedical research firm based in Rockville, Maryland, that helped clients design, conduct and analyze epidemiologic studies of the causes of cancer and other diseases.

In 1998 Loren Lipworth, ScD, a colleague at IEI, moved with her husband to Nashville and got a research job at VUMC. She suggested that Blot call Moses and offer to help expand Vanderbilt Cancer Center’s epidemiology program — a prerequisite for attaining the highest NCI designation as a “comprehensive” center.

Moses said he was not impressed by Blot’s initial offer simply to help recruit more cancer epidemiologists. But when he proposed tracking cancer cases and outcomes over time in a “cohort” of thousands of Blacks recruited through community health centers, “that really got my interest,” Moses recalls.

At the time, many Blacks, especially in the South, were reluctant to volunteer for medical research, in part because of the public outcry over the federal government’s infamous, 40-year “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” which was halted in 1972.

“Still for some people (that study) impacts their willingness to trust government and even … Vanderbilt and Meharry,” Blot says. He believed that working with a community health center would overcome that reluctance because “it was a trusted setting.”

In 1999 Blot presented his proposal to officials of the Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance, which had recently been established to explore ways the two medical schools could collaborate in medical education, research and community health partnerships that served the underserved and uninsured.

After Blot’s presentation, George Hill, PhD, a microbiologist who at the time was Meharry’s vice president for sponsored research, asked him why he wanted to undertake such an ambitious study.

“He thought it was critical to look at diseases that disproportionately affect Blacks,” Hill recalls. “It was very clear that he was sincere. (Blot) was a breath of fresh air.”

Hill later was recruited to Vanderbilt where he served in several key leadership roles, including the university’s first vice chancellor for equity, diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer, before retiring in 2017.

The Study Begins

The family of the late E. Bronson Ingram, a prominent Nashville industrialist and former chair of the Vanderbilt University Board of Trustees, pledged to provide the first $56 million for expansion of what would become the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center in 1999.

With the alliance’s blessing and significant Ingram family support, a pilot study was conducted to test the feasibility of assembling a huge cohort of research participants.

The study was undertaken at the Matthew Walker Comprehensive Health Center, blocks from the Meharry campus, with the support and assistance of the center’s CEO, the late Michelle Marrs. The center is named for the late Matthew Walker, MD, a pioneering Meharry surgeon and community health advocate.

Blot was the study’s co-investigator with the late Margaret Hargreaves, PhD, associate professor of Internal Medicine at Meharry known for her health disparities research.

Meanwhile Blot was calling on colleagues to join the cancer epidemiology team at VICC. Among them: Wei Zheng and his wife and scientific colleague, Xiao-Ou Shu, MD, PhD, MPH, who Blot had met in Shanghai while he was at NCI.

After graduating from medical school in Shanghai in 1983, “I worked as a research assistant in a large lung cancer study led by Bill and my former mentor Dr. Yu-Tang Gao at the Shanghai Cancer Institute,” Zheng says.

“While I was a PhD student at Johns Hopkins University, Bill offered me a research position at NCI. Under Bill’s exceptional mentorship, I completed more than 10 research papers and co-authored about 15 additional papers in 18 months.”

In 1999 Zheng and Shu were at the University of South Carolina in Columbia and were leading a large cohort study, the 75,000-member Shanghai Women’s Health Study, which had been supported by NCI since 1996.

Wei Zheng, MD, PhD, MPH, (left) and Xiao-Ou Shu, MD, PhD, MPH, (standing) were recruited to Vanderbilt by Bill Blot, PhD. Photo by John Russell.

“I thought they would be ideal to come to Nashville,” Blot says. “They agreed … and by the summer of 2000 Wei and Xiao-Ou had come, and they also brought several of their colleagues (and their cohort study) with them.”

With the recruitment of some of Blot’s IEI colleagues, VICC’s roster of cancer epidemiologists increased fivefold — to 10 — in little more than a year.

By late 2000, armed with successful results from their pilot feasibility project, Blot, Hargreaves and their colleagues applied for a major grant from the NCI for the cohort study. Ten months later the NCI approved their application on the first go-round, without asking for modifications or additional supporting material.

The first grant, announced in October 2001, provided several million dollars annually over five years to enable the recruitment and following of tens of thousands of people — two-thirds of them Blacks — by community health centers in Tennessee and five surrounding states.

According to the VUMC announcement, “It will be the first study of its kind in the southern United States and the largest population-based health study of African Americans ever conducted.”

At the time, the $22-million SCCS award was the largest research project grant (R01) VUMC had ever received, Blot says. With additional funding from NIH and Caterpillar Inc., over time the SCCS expanded through 12 southern states and its cohort grew to 85,000 adults.

Among the research findings coming out of the SCCS:

- Blacks in the South had markedly lower blood levels of vitamin D than whites. Vitamin D is created in the body from sunshine exposure but also is obtained from vitamin-fortified foods including milk. Inadequate vitamin D levels have been linked to a higher risk of some cancers and other diseases.

- Colonoscopy screening was only half as common in Blacks as among white participants, and was even lower among Blacks with a family history of colorectal cancer.

- A one-time PSA (prostate specific antigen) measurement at around age 45 was predictive of subsequent long-term prostate cancer risk, providing a rationale for who to screen, and who not to.

- A single “polypill” combining low doses of three high blood pressure medications and one cholesterol-lowering drug reduced the estimated risk of cardiovascular disease by 25%. Polypills are more convenient, especially for patients with limited access to health care.

The SCCS also revealed that existing lung cancer screening guidelines systematically excluded many Blacks, Blot said. SCCS researchers suggested a fix, which was adopted this year by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to help make screening more equitable.

Partners and Mentors

Thanks in part to the success of the SCCS, in 2006 Meharry and VICC successfully competed for renewal of their five-year NCI-funded Minority Institution/Cancer Center Partnership grant, which that year added Tennessee State University. Today the Meharry-VICC-TSU Cancer Partnership continues to focus on eliminating cancer disparities.

The SCCS — and Blot — also have provided valuable training opportunities and helped spark the careers of many young scientists.

The cohort study “made it possible for many mid-career and senior scientists in cancer research to seek and obtain their individual R01 grants to support further studies on cancer health disparities,” Meharry’s Adunyah says.

“The thousands of human tissue samples collected and frozen by the SCCS will continue to be used for cancer research throughout the decades,” he says.

“Bill has made a tremendous impact on the career development of many others, including myself,” says VUMC’s Shu, principal investigator of another large cohort study, the 61,000-member Shanghai Men’s Health Study, launched in 2002.

“I continue to benefit greatly from his insights and expertise,” adds Zheng.