The Invisible Wildfire

November 22, 2017 | Tom Wilemon

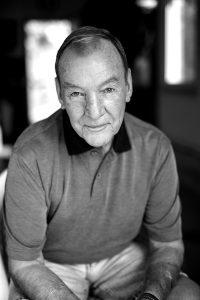

Don Cox didn’t intend to quit smoking. He enjoyed lighting up. A cigarette helped him relax, socialize, figure out a problem or just have a moment to himself. His hand felt empty without one.

“Every year, my doctor would say ‘You got to quit smoking.’ I just let it go over my head,” Cox said.

But he did relent when his doctor insisted he undergo a CT scan to check for lung cancer. Cox, a Franklin, Tennessee, resident, started smoking at age 20 and kept lighting up for 52 years. He lives in a region with some of the worst smoking rates in the nation. At least one out of every five adults in Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi smokes, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Kentucky, which has the nation’s highest smoking rate, about one in four smokes. It’s like an invisible wildfire.

Smoking cessation clinics are scarce in the region. Few of the people considered at the highest risk for lung cancer—those who have smoked about a pack a day for 30 years and qualify for CT scans—undergo screenings.

Photo by Daniel Dubois

Cox didn’t have to pay anything for his CT scan. Covered by private insurers and Medicare, it is a painless and potentially life-saving diagnostic tool that can detect tumors at early stages. Insurers began covering yearly screenings in 2015 after researchers at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) and other medical centers proved they reduced lung cancer deaths by 20 percent in patients who were at high risk, but had no symptoms of the disease.

Although smoking cessation treatments are much less expensive to insurers than CT scans, the United States health care system doesn’t set the stage for the treatments to be a sustainable intervention, said Pierre Massion, M.D., Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Medicine and director of the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) Early Detection and Prevention Initiative.

“There is a tripod, which is really important for smoking cessation,” Massion said. “The first leg is the patient’s education and counseling. The second is the treatment of tobacco addiction with nicotine replacement therapy and other medications. The third one is a close follow-up to reinforce motivation and assess for potential side effects.”

Reimbursements for smoking cessation are too low to make it economically feasible for clinics to specialize in this service, he said. Massion and colleagues identified the CT scan procedure as an opportunity to help smokers quit. They are also advocating for better access to treatment, identifying smokers hospitalized at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) to talk with about cessation and conducting research to evaluate the most effective interventions. In 2018, VUMC will open an outpatient tobacco treatment clinic for patients with any type of cancer, an initiative supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute. The clinic will be directed by Hilary Tindle, M.D., MPH, associate professor of Medicine and the founding director of the Vanderbilt Center for Tobacco, Addictions and Lifestyle (ViTAL.)

A shared decision

The Vanderbilt Lung Screening Program, where Cox underwent the CT scan, is a comprehensive program where radiologists and nurses engage patients in shared decision-making, help them keep track of follow-up scans, refer them to specialists when necessary and provide tobacco cessation counseling.

Cox’s CT scan showed no signs of lung cancer. His talk with a nurse at an appointment during the summer of 2016 convinced him to try quitting.

“After she was finished with the procedure, we were just talking,” he said. “After a while, I realized she had given me several reasons to not smoke. I had been told by my doctor and others for 14 years that I should quit. I knew it was bad for me but I enjoyed smoking.”

The discussion hadn’t been hurried. The nurse and the patient got to know one another.

“I am 77,” he said, a year after being tobacco free. “I have a 46-year-old wife and an 18-year-old daughter. I’d like to live a little bit longer, get her out of college and get her married—all that kind of stuff.”

The Vanderbilt Lung Screening Program launched in 2013. Since then, more than 750 smokers have undergone CT scans with cancer having been diagnosed in 25 of those patients. Although the primary goal of the program is to diagnose the cancer at an early stage before symptoms arise and then refer patients to treatment, most patients don’t have the disease.

“I don’t think enough attention is given to the amount of stress relief we are providing to most people, who are concerned about their lifetime of smoking, especially if they have seen a family member or friend go through lung cancer,” said Alexis Paulson, MSN, clinical coordinator of the Vanderbilt Lung Screening Program.

Patients who enroll in the program come back for yearly exams and are sent reminders.

“I have found a lot of personal satisfaction in getting to spend time with these patients,” Paulson said. “Getting a detailed smoking history usually yields a detailed life history. My patients are in their 60s and 70s and have had long, interesting lives. The biggest joy I get is when they have a normal scan, and I see them in the next year and they’ve quit smoking in that interval.”

Although someone has to have been a heavy smoker for 30 years for insurance to cover the cost of the CT scan, the Vanderbilt Lung Screening Program will do it for about $260 for other smokers.

Yearly monitoring

Kim Sandler, M.D., assistant professor Radiology and Radiological Sciences and co-director of the Vanderbilt Lung Screening Program, said it’s important that patients commit to yearly scans even if the first one indicates no signs of cancer.

“Having a repeat scan is absolutely essential,” Sandler said. “We are looking for a change. We have a number of patients who maybe have an abnormality that we consider to be something that we should watch. They may come back for a repeat study in three or six months.”

One concern among some patients is over-treatment—worrying that hospitals look for reasons to do surgery. VICC has advanced imaging technology that allows physicians to better distinguish lung nodules that may be cancerous from ones that don’t require surgery. Massion leads a team of researchers focused on initiatives, studies and protocols to avoid unnecessary biopsy or surgery.

“We know we will find a lot of false positives,” Sandler said. “The nice thing about having this study done here at Vanderbilt is the imaging is read only by chest specialists who primarily focus on reading CT imaging of the chest, so we have seen a lot of benign pulmonary nodules.”

A more robust effort to give people better access to smoking cessation treatment, including outpatient clinics that specialize in counseling, would cost the health care system much less over the long run than doing CT scans to check for cancer after smokers go through a pack a day for 30 years, Massion said.

Two-for-one for women

Another focus is to encourage women to have CT scans. Sandler would like to establish a referral system so that women coming to the Vanderbilt Breast Center for mammograms can be advised of the need for lung screenings if they qualify.

“More women die from lung cancer than from breast cancer,” she said. “Breast cancer is more often diagnosed, but the death rate for lung cancer is much higher than for breast cancer.”

A dual referral system would also offer the opportunity for women smokers to be offered cessation counseling.

Tindle runs ViTAL, a program that aims to link hospital patients to smoking cessation programs.

“Hospital interventions for smoking cessation are effective,” she said, citing a study that showed if hospitalized smokers are counseled at the bedside for six minutes or more and then followed after discharge in the first month, the odds of cessation at six months are 37 percent higher than without an intervention. ViTAL also identifies patients who qualify for CT scans and refers them to the Vanderbilt Lung Screening Program. Paulson then reaches out to those patients to schedule the screenings.

Jennifer Lewis, M.D., a Veterans Affairs Scholars Fellow and VUMC instructor, is working with Massion and Tindle to study providers’ attitudes and practices related to smoking cessation.

“We have had a good response rate from a provider survey we administered in the spring of 2017 and are currently analyzing our data,” Lewis said. “We hope to employ future provider interventions that will incorporate education on the effectiveness of tobacco cessation in reducing mortality.”

Cox weaned himself off cigarettes by chewing nicotine gum and reducing his smoking to three cigarettes a day. He smoked his last three on Sept. 4, 2016.

“They didn’t taste good and didn’t satisfy my urge to smoke,” he said.

However, he continued to use the nicotine gum for almost a year until recently switching to a sugar-free brand.

“This may sound easy, but believe me it wasn’t,” he said. “The main thing that keeps me from not smoking again is I don’t ever want to go through quitting again.”