Decision Tree

Helping prostate cancer patients select the treatment that’s best for them

June 22, 2011 | Leigh MacMillan

Kort Nygard opted to wait until his prostate cancer needed treatment. Then he decided to have open surgery.

Jim Davidson chose radiation therapy, the external beam type.

Sam Dick selected robotic surgery.

Three different patients with prostate cancer, three different treatment choices.

The decision that faces a man diagnosed with localized prostate cancer is daunting. He can choose to monitor the cancer and defer treatment until the cancer progresses (an option known as active surveillance). Or he can choose one of several different treatments for prostate cancer – including multiple types of surgery and radiation therapy – that all have a risk of side effects such as urinary problems like incontinence, bowel problems and erectile dysfunction.

Kort Nygard opted to wait until his prostate cancer needed treatment. Then he decided to have open surgery. Click to read his story. (Photo by John Russell)

“It’s a swamp, and it’s tough on patients,” says David Penson, M.D., MPH, a urologic surgeon/oncologist at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

To navigate that swamp, Nygard, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist, developed his own “decision tree” – a tool for assessing his preferences about treatment options, outcomes and side effects.

“What came out on top for me was I wanted to be as sure as I could that the cancer was gone,” Nygard said.

The trouble for most patients is that no such decision tree exists. Information about outcomes and side effects of prostate cancer treatments is scattered, making it difficult to compare different treatment options. Penson aims to change that. He is leading an ambitious new study to get at “what works best, in which patients, and in whose hands,” he says.

“You want to be able to say to a patient: ‘Consider how you feel about your cancer, your work status, your marital status, your clinical stage and grade. Now factor in your individual risk of being impotent and incontinent if you have surgery, your risk if you have radiation, your overall risk of cancer recurrence, and your likely satisfaction with care. Now use this personal information to guide you in your choices.’

“That way the patient can make an intelligent decision.”

Kittens and tigers, oh my

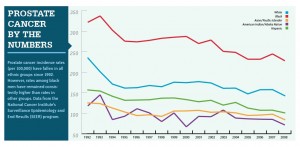

Prostate cancer is the most common solid tumor, and the second leading cause of cancer death, among American men. The National Cancer Institute estimated that in 2010, 217,730 men would be diagnosed with cancer of the prostate and 32,050 men would die from the disease.

But prostate cancer may be even more common than the diagnosis rate suggests. Autopsy studies have shown that about two-thirds of men in their 60s – who die of other causes – have prostate cancer.

These cancers went mostly undetected before the introduction of the PSA (prostate specific antigen) blood test – a screening

test for prostate cancer – in 1986. If prostate cancer was found, it was usually during surgery for benign prostatic enlargement (a condition that causes urinary symptoms) or after the cancer had already spread.

Now, routine PSA screening triggers alarm bells and referrals to urologists, who often recommend a biopsy to check for cancer. More than 80 percent of the cancers that are detected by biopsy are at a very early stage, haven’t spread outside the prostate and aren’t causing any symptoms, Penson says.

“Before screening, we didn’t know about these cancers. Now the screening helps to find them earlier. Is that a good thing, or not? Are we finding cancers which are dangerous – they’re going to spread in the patient’s lifetime – or are we finding cancers which in the end are sort of like an age spot?”

Likening prostate cancer to the cat family, Penson says, “The problem is – while I can get a hint of whether it’s a tiny little kitten or whether it’s a tiger, I can’t give you a 100 percent guarantee one way or the other.”

The hints come from the PSA level and how fast it has climbed, what the cancer cells look like on microscopic examination (Gleason score), and what proportion of the prostate appears to contain cancer (how many of the biopsy “cores” have cancer cells in them).

The “tiny little kitten” prostate cancers are most likely indolent – clinically meaningless slow-growing cancers that will never cause any symptoms or spread outside the prostate. Estimates from studies conducted by Penson and others suggest that 25 percent to 40 percent of prostate cancer cases fall into this category – they are “over-diagnosed” and don’t need to be treated.

But there’s no certain way to tell which cancers those are.

Researchers have been searching for biomarkers that will distinguish indolent from aggressive prostate cancer for more than 20 years, Penson says. “Whoever gets that right will do an incredible service for medicine.”

The latest prostate biomarker findings made news in February, when researchers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute reported that a panel of four molecular markers, in combination with the Gleason score, could accurately predict a cancer’s aggressiveness 90 percent of the time. They hope to develop a clinical test in the next year or so.

To treat or not to treat

Since there’s always some risk of disease progression – even if it’s a very small risk – why not go ahead and treat every prostate cancer?

Two costs: a physical toll for many patients in terms of side effects, and an overtreatment price tag of more than $600 million a year in the United States.

Jim Davidson chose radiation therapy, the external beam type. Click to read his story. (Photo by John Russell)

Standard treatments for prostate cancer include: surgery to remove the prostate (prostatectomy), performed through an open incision or using a robotic-assisted laparoscopic procedure; radiation delivered from outside the body (external beam) or by implanting radioactive “seeds” into the prostate (brachytherapy); and cryosurgery, an approach that uses extreme cold to kill tumor cells.

The prostate cannot simply be cut out or destroyed without some degree of collateral damage. It is an intimately integrated part of the male reproductive system.

A healthy prostate – about the size of a kiwi fruit – sits below the bladder and surrounds the urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder out of the body). The prostate produces and stores alkaline fluid that becomes part of the semen.

Any treatment of the prostate gland runs the risk of damaging nerves and nearby tissues, causing problems with urinary function, bowel function and erectile function, very personal side effects that impact quality of life.

So if a prostate cancer has a low risk of spreading and isn’t likely to bother a patient in his lifetime, active surveillance – monitoring the cancer and deferring treatment – can be a good option.

The old terminology for active surveillance, “watchful waiting,” has fallen out of favor, Penson says, because it seems to imply, “I’m watching, and I’m waiting – to die.

“With active surveillance, we’re checking PSA levels, we’re doing more biopsies, and if things look worse, we’re going to jump on this. I’m a big proponent of active surveillance,” Penson says.

Still, active surveillance is not always a straightforward approach.

“We do not have good data to show us whether deferring treatment until we see a change and then moving ahead, how much that compromises things,” says Joseph Smith, M.D., chair of Urologic Surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Multiple biopsies – perhaps performed annually – can also contribute to side effects like erectile dysfunction.

“Biopsies take a toll on people too,” Smith says. “Active surveillance is not always an easy route to follow.”

And for some men and their families, it’s simply too difficult to live with a diagnosis of cancer without treating it.

“There’s no question we end up over-treating men, that there are men who undergo surgery and we cure them of their cancer, but it was a cancer never destined to bother them,” Smith says. “It’s an individual patient decision, and each man has to decide what’s going to make him the most comfortable.”

Eeny, meeny, miny, moe

If active surveillance isn’t a good option – for personal reasons (not comfortable with deferring treatment) or clinical reasons (cancer was initially a higher risk or has progressed after treatment) – the patient must choose a treatment.

“Lady” and “tramp” are helping Robert Matusik, Ph.D., and colleagues study how prostate cancer develops. Click photo for their story. (Photo by Joe Howell)

The options can be overwhelming, Penson says.

Surgery? Open or robotic? Radiation therapy? Internal seeds or external beam? Cryosurgery? What about some of the newer technologies? Radiation with protons? High intensity focused ultrasound?

“For some of these treatments, there are companies that market directly to patients. And because patients have some time to think about their options, they can fall victim to the ‘latest and greatest’ syndrome,” Penson says.

He laughs about billboards he’s seen in Florida that say “have your prostate removed here; have your seeds done here.”

How does a patient choose?

They listen to what physicians say, talk with family and friends, and do research online, but it’s murky.

Physicians want what’s best for the patient, but they have their own biases about what the best thing is, Penson says. Studies have shown that surgeons are more likely to recommend surgery, while radiation oncologists are more likely to recommend radiation therapy.

“I think the reason we do what we do is because we believe in it,” says Eric Shinohara, M.D., a radiation oncologist at Vanderbilt-Ingram. “That’s one of the good parts of being at a place like Vanderbilt, where it’s a real team effort, and we appreciate what each modality can accomplish. There’s no class solution for prostate cancer.”

Surgical removal of the prostate may offer more peace of mind that cancer has been cured. Radiation therapy offers a less invasive approach without significant recovery time. Some patients choose radiation therapy – particularly brachytherapy – because it’s perceived to preserve erectile function more than the other therapies, though this issue is highly debated, Shinohara says.

Very few clinical trials have attempted to compare one treatment choice to another, Penson says. He was part of a study about 10 years ago that was designed as a randomized trial to compare surgery with brachytherapy in men with low risk prostate cancer.

“We wanted to put 2,000 patients on the study; we accrued 60 patients,” Penson says. “Men don’t want a computer to make this personalized decision; it’s a very hard sell.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that in prostate cancer, randomized clinical trials alone are not the answer. A well-designed observational study may provide more valuable information.”

David Penson, M.D., MPH, is leading a study to compare the effectiveness of treatment approaches for localized prostate cancer. (Photo by John Russell)

That’s where the new trial Penson is leading – CEASAR – comes in.

Hail, CEASAR

CEASAR stands for Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery And Radiation (in prostate cancer). The study is broader than the acronym suggests – it aims to compare the effectiveness of all approaches to treating localized prostate cancer, including active surveillance.

Penson and Vanderbilt-Ingram received a $7.6 million stimulus grant to coordinate the study. Funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the three-year grant is one of 11 CHOICE awards – studies comparing the effectiveness of treatments for high priority conditions identified by the Institute of Medicine. CEASAR is the only prostate cancer treatment study.

Daniel Barocas, M.D., MPH, assistant professor of Urologic Surgery, and Tatsuki Koyama, Ph.D., assistant professor of Biostatistics, are co-investigators for CEASAR.

CEASAR will use a network of state and city tumor registries and a national prostate cancer registry to enroll men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer in a six-month period – about 4,000 men. The study will follow the men for a year, though Penson is hopeful that if the study is successful, additional funding will allow it to continue for a longer period of time.

The tumor registries cover the states of New Jersey and Louisiana and the metropolitan areas of Atlanta and Los Angeles, offering diversity of race, socioeconomics and education. The national registry, coordinated by investigators at the University of California, San Francisco, will focus on patients who select new treatment technologies.

Two new treatments for advanced prostate cancer were approved in 2010 and more are on the horizon. Click image to read more.

The study team will use questionnaires to collect patient-reported information at baseline (before treatment), and six and 12 months later. The questionnaires will ask about what Penson calls “squishy” variables, for example, general quality of life, sexual function, urinary function, social support, trust of the health care system, anxiety about prostate cancer, and economic burden of prostate cancer.

The investigators will also collect clinical data, including technical details of treatment, complications, short-term cancer recurrence rates and quality-of-care indicators. It’s the first comparative effectiveness study in prostate cancer to put quality into the mix.

“It’s a complicated study,” Penson says. “What we plan to do is identify which therapies work best in which types of patients. And we’ll help patients identify the kinds of cancer centers and physicians that provide the best prostate cancer care.”

He hopes that the data will become part of an online tool – a decision tree of sorts – that will guide patients through the treatment options and their effects on sexual function, urinary and bowel function, and cancer control “at X, Y and Z hospitals or in Dr. PDQ’s hands.

“It boils down to generating useful information for patients, providers and policy makers, so that we can get the right treatments to patients.”