Taming the Tiger

New treatments for advanced prostate cancer

June 22, 2011 | Leigh MacMillan

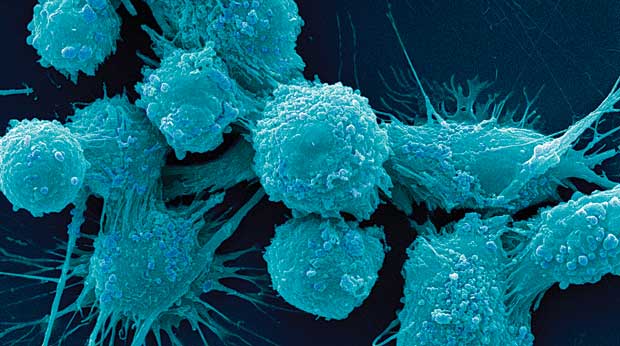

Human prostate cancer cells. (Image by Dr. Gopal Murti/Visuals Unlimited, Inc.)

About a third of patients who are treated for localized prostate cancer will have a recurrence, says David Penson, M.D., MPH. A small percentage of patients already have metastatic prostate cancer – cancer that has spread beyond the prostate gland – when they are first diagnosed.

“Metastatic prostate cancer is a tiger that’s out of the cage; we can’t cure it,” Penson says.

But it can be treated, with the goal of controlling the disease for as long as possible, says Christina Derleth, M.D., a medical oncologist at Vanderbilt-Ingram.

The first line of therapy for metastatic prostate cancer is hormone therapy. Medications or surgical removal of the testicles are used to suppress or remove testosterone (androgen) production.

“It’s kind of like putting a guy into menopause,” Derleth says, with similar side effects – hot flashes, irritability, and weight gain. And though it’s not a cure, about 80 percent of patients respond to hormonal therapy – their disease does not progress – for variable periods of time.

“Some patients may stay on hormonal therapy for as long as a decade or more with controlled disease,” Derleth says, though she notes that the average response is 18 to 24 months.

Once a tumor starts growing on androgen deprivation therapy or in the castrate state, it is called “castrate-resistant prostate cancer.” It may still respond to a second line of hormonal therapy – drugs that block the androgen receptor or that block production of androgens elsewhere in the body (the adrenal glands).

If the cancer progresses on a second hormonal therapy, treatment options are limited to chemotherapy (Taxotere and Jevtana, which was approved in 2010) and an immunotherapy called Provenge (also approved in 2010).

Provenge is a “therapeutic cancer vaccine.” It doesn’t prevent disease like a traditional vaccine; instead, it harnesses the activity of the immune system to kill cancer cells.

Christina Derleth, M.D.

The patient’s white blood cells (immune system cells) are collected and sent to a laboratory, where they are exposed to a prostate cancer protein linked to an immune cell growth factor. This exposure “activates” the white blood cells so that they recognize and kill cells containing the prostate cancer protein (about 95 percent of prostate cancer cells). The activated cells are returned to the hospital and are infused into the patient. A complete treatment, three infusions in one month, causes relatively minimal side effects compared to chemotherapy.

“This is truly personalized medicine,” Penson says, “it doesn’t get much more personal than using the patient’s own cells.”

In clinical studies in which Penson participated, Provenge extended the survival of patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer four months compared to patients who were not treated, similar to the survival advantage of the chemotherapy Taxotere.

Derleth notes that Provenge did not impact the growth of the cancer – the cancer progressed during treatment – so patients with metastatic disease that is causing symptoms may not be good candidates for the treatment.

And Provenge is costly – $93,000 for the complete treatment. Is four months worth $93,000?

Penson sighs. “I’ll dodge the question. But I will say that if we’re going to look at Provenge in that cost-effectiveness light, we can’t stop there, we have to look at everything we do in that light – all the other drugs, all the other interventions.”

For patients with metastatic prostate cancer, he adds, “Provenge represents a unique ray of hope. Many of these patients are making co-pays, so they’re making a conscious decision to lay out the resources. That tells you something.”

Derleth and Penson are optimistic about treatment options for metastatic prostate cancer.

“2010 was a big year – we got two new interventions,” Derleth says. “This was huge considering we hadn’t had any new drugs approved for prostate cancer since 2004.”

And there are new hormone therapies on the horizon, along with another immunotherapy.

“This is the most enthusiastic I’ve been about advanced prostate cancer in my career,” Penson says. “I see things coming. They’re not curative, but we’re going somewhere. There are actually options, and soon we’ll be combining options and hopefully getting durable survival advantages and maybe even cures.

“We’ll see.”

Categories: Departments • Spring/Summer 2011

Previous Post: Thriving After Cancer

Next Post: Friendships, Legacies