Molecular Mission

Ben Ho Park shares his vision for giving more people access to precision oncology

March 1, 2021

Illustration by James Fryer

Ben Ho Park, MD, PhD, has a microscopic focus on solving the molecular mysteries of cancer and a panoramic approach to sharing that knowledge. He is committed to the democratization of precision oncology — helping more people gain access to the highly personalized medicines that are transforming cancer care.

“It shouldn’t be that just the well-resourced and well-connected get access to this information; it should be that everyone is able to get the best state-of-the-art care,” said Park, the Donna S. Hall Professor of Breast Cancer Research at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC).

Park became director of the Division of Hematology and Oncology in October 2020 after leading the division on an interim basis and having launched successful new initiatives at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

He has started both regional and global networks to link patients with molecular tumor boards, which are composed of highly specialized physicians and scientists, who have expertise in genetics, precision therapies, pathology, surgery and oncology. These boards review challenging cancer cases and guide treatment plans.

One challenging case, the plight of a young girl from Bangladesh, inspired Park to bring these cancer experts out of the boardroom and onto the internet. Through work with the Global Cancer Institute in the summer of 2016, he became aware of the girl who had a very rare type of breast cancer.

“It’s called juvenile secretory breast carcinoma. It is extremely rare, and nobody on this breast tumor board except me — a geeky physician scientist — knew what this was,” he said. “I happened to have had training in laboratory and genetics, and about 15 years prior a seminal paper described the molecular alterations that define these tumors. The other crazy story behind this is — I am not particularly religious, but I think this story actually had divine intervention — I happened to be on the scientific advisory board of a small startup company that had an amazing drug. They were looking for these types of alterations in their cancers.”

Park connected the girl and her family with oncologists in the United States who were conducting clinical trials for the drug, and she was enrolled.

“It was amazing,” he said. “She had a complete response and is back home in Bangladesh, taking just a pill and doing OK. It’s really an incredible story. This was a Lazarus-like response because she was surely going to die. This is a disease that, once it spreads, is not sensitive to chemotherapy or radiation. She’s 18 now.”

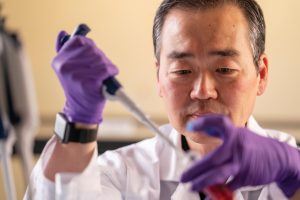

Ben Ho Park, MD, PhD, newly named director of the Division of Hematology and Oncology at Vanderbilt. Photo by Joe Howell.

Park, who is now the co-chief medical officer of the Breast Program for the Global Cancer Institute, first established a molecular tumor board at Johns Hopkins then organized one at Vanderbilt after he was recruited in 2018. The Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center’s Hereditary and Oncologic Personalized Evaluation Molecular Tumor Board (VICC-HOPE MTB) meets weekly to discuss challenging cancer cases from both within and outside VUMC. In addition, the international virtual VICC MTB, called “Our Cancer Genomes” meets online monthly using a secure telehealth format to discuss patient cases submitted by the international cancer community.

“Simply put, the meetings are usually an hour format where all these medical disciplines come together to discuss cases,” Park said. “It is done in an anonymized manner so that we are limiting patient information. It provides a consultive, an almost blitz approach, so that everyone can weigh in on a patient case. We usually go through about four or five cases in an hour. To really get the best value out of a molecular report or test, you need more than just one doctor. You need someone who is trained in genetics as well as clinical oncology and a subspecialist oncologist who is an expert on that particular cancer.”

Career Achievements

Growing up in Saginaw, Michigan, where his father was a colorectal surgeon, Park knew early in life that he wanted to be connected to a more global community.

“I always felt like I was different,” he said. “One reason was because we were probably one of two Asian families growing up there. Two, I felt like my life’s ambition was to do something positive that was bigger than what I felt I could achieve there.”

His father, who is now retired, put in long hours as a surgeon.

“My father is one of the hardest working people I’ve ever met in my life,” Park said. “He always discouraged us from going into medicine. I’m one of four kids. He, I think, felt like it was such a long training path, particularly being a surgeon. However, once I decided to be a doctor and go into medical school, then my father thought I should be a surgeon. To this day, I don’t think he has ever understood why I got a PhD.”

After receiving his undergraduate degree with honors from the University of Chicago in 1989, he completed a dual MD, PhD training program at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1995. He completed a residency in internal medicine and hematology/oncology fellowship training at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

In 2001, Park finished a postdoctoral research fellowship in cancer genetics at Johns Hopkins. He then joined the faculty in the Department of Oncology at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, where he became an internationally renowned breast cancer expert. In 2004, he was the first to identify a high frequency of PIK3CA mutations in breast cancer and then discovered their contributions toward oncogenic phenotypes. His work, including the generation of genetically modified cell lines, has been widely cited, and requests for his cell lines have led to important discoveries by other investigators. He made fundamental contributions to the field of drug resistance and pioneered the use of liquid biopsies to help guide future management of breast cancer therapies.

Park was recruited to Vanderbilt-Ingram in 2018 to be associate director for Translational Research, co-leader of the Breast Cancer Research Program and director of Precision Oncology. He follows Kimryn Rathmell, MD, PhD, Cornelius Abernathy Craig Professor of Medicine, in leading Hematology and Oncology after she was promoted to chair of the Department of Medicine at Vanderbilt in August of 2020.

“Dr. Park has demonstrated incredible leadership in steering the division through the pandemic as interim director,” Rathmell said. “His vision for taking this strong unit into the future is exciting. Opportunities in hematology and cancer research and the prospects for new treatment innovations have never been more vibrant. The Vanderbilt faculty are at the forefront of these advances, and Dr. Park is exactly the person to lead this division through this transformation in care.”

Jennifer Pietenpol, PhD, director of Vanderbilt-Ingram and Executive Vice President for Research at VUMC, also noted Park’s impact.

“Dr. Park is a research leader who inspires his colleagues and a physician who is committed to providing patients with high quality and personalized care,” said Pietenpol, the B.F. Byrd Jr. Professor of Oncology and holder of the Brock Family Directorship in Career Development. “In the relatively short period he has been with Vanderbilt, he has implemented initiatives that are already transforming care for people with cancer both within and beyond the catchment area we serve.”

Approach to Mentoring

In addition to treating patients and leading the division, Park continues to do research and is a mentor to the young scientists who work in his lab.

“I learn as much or more from my mentees as they learn from me,” he said. “I think that’s a rewarding aspect to see your mentees become your colleagues, to watch them succeed and learn from them. I make mistakes just like everyone else. I have the same insecurities and vulnerabilities just like everyone else, but I have come to realize that it’s OK to show those and share those with my mentees and vice versa. That creates such a strong culture of congeniality and safety and family.”

It’s a space where he cultivates a fun work environment. At the entrance to his office, a sign shaped in a three-dimensional, curved arrow imprinted with “Park” greets people as though directing them into a vehicle garage. The lab’s website features the researchers in goofy costumes and poses. And its leader is known for incorporating backdrops for Zoom meetings that make it look as though he’s inside a starship module.

But the people who have worked in his lab realize the importance of what they do. Cancer can strike anyone with tragic consequences, even someone who is young and is connected to the nation’s top cancer specialists.

“I just came back from a funeral for one of my former mentees, who tragically died of sarcoma just a couple of weeks ago,” Park said. “It was probably one of the hardest things I’ve had to do, to give his eulogy just two days ago. At the same time, I felt so honored to be the one to do that.”

The young researcher had worked in Park’s lab in Baltimore and was about to do a postdoctoral fellowship.

“The strong message from this experience is that we have to do more, that we have to do better,” he said.

Division Goals

The physicians and scientists at Vanderbilt-Ingram have expertise in every type of cancer, including rare cancers.

“I want our division to be the place that patients, researchers, care providers and referring physicians think of when they have difficult cases of hematologic disorders or cancers,” Park said. “Vanderbilt should be at the top of the list. There has been a sea change that has happened over the past decade of understanding how we treat cancers effectively. Understanding the molecular underpinnings of each and every person’s cancer gives us the ability to attack those particular gene mutations.”

Vanderbilt also has unique resources for cancer research, he noted, including BioVU, a biobank with over 250,000 DNA samples. It is one of the largest electronic health record-based biobanks in the world housed at a single center. Each blood sample collected for BioVU is de-identified and coded according to a protocol to protect privacy so that the data cannot be linked back to the patient.

“I had never even heard of BioVU until I started interviewing here,” Park said. “It is one of the most amazing biobanks in the world. We’re a best kept secret, but I don’t think we should be a best kept secret. We should find a way to tout in a very humble, modest way how great we are. I know that sounds a little bit weird. It’s somewhat of an oxymoron, but I do think we have the talent, the resources and the people — above all else — to really do amazing things here.”

Park stresses the need for researchers, particularly those involved in molecular oncology, to take the time to nurture young scientists and physicians.

“Yes, we are about curing diseases; yes, we are about tackling the difficult problems that nobody else necessarily wants to,” he said. “But I want to put front and center that we are also about training the next generation. I find that to be so critically important. With every job that I walk into, I start thinking immediately about who my successor is going to be because I am not going to be around forever. What I don’t want to happen is for things that have built up and that have so much value go by the wayside because there is no one else to take them on. That mandates that we think about the future and train people in molecular oncology and think about how we sponsor those individuals to start their own programs across the country and the world.”