Unwelcome Encore

Beating one cancer to fight another

May 22, 2018 | Nancy Humphrey

Photo by John Russell

The phrase “lightning never strikes twice” means little to Thomas Brewer of Charlotte, Tennessee, because for him, it did — once in 2000 and again in 2017. The “lightning” in Brewer’s case was cancer — first, esophageal; then, colon. For some, developing a secondary cancer — not a spread or recurrence of a first cancer, but a different “second primary” cancer that is unrelated to the first — is reason to give up. Not for Brewer.

The diagnosis was an unwelcome encore for Brewer, a musician who plays bass guitar in a rock ‘n’ roll band. But he saw it as a challenge, not a death sentence. Overcoming esophageal cancer 17 years before he had to fight colon cancer made him even more determined to beat it the second time. Having completed chemotherapy at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) in February, the 66-year-old retiree believes he has.

In 2000, Vanderbilt surgeons removed his esophagus and built a new one from his stomach. Then he had chemotherapy and radiation. “I was told that 80 percent of people who have this cancer die. I wanted to be in the 20 percent,” he said.

Seventeen years later, Brewer’s colon cancer was caught early and he had surgery to remove 18 inches of colon, followed by six months of biweekly chemotherapy. “It was kind of tough, but I decided to go on and live my life,” he said. “I beat it once. I can beat it again.”

The first diagnosis was actually more emotionally difficult, he said. “The minute someone tells you that you have cancer, your very next thought is ‘I’m going to die,’” Brewer said. “It’s mind boggling. And it’s hard to plan your future, because you’re not sure what your future is.

“You see so many losses of life around you from cancer. But it (odds of survival) has gotten so much better, so when I got the second diagnosis, I had already beat esophageal cancer, and that’s a hard one to beat. I’m a firm believer that if the doctor tells you to do something, you do it. I said prayers and it worked out perfect.”

Brewer, who walks for exercise and generally keeps himself busy with band practices and other activities, said he believes that a “positive outlook is the greatest medicine against cancer.” He also had a lot of family support during his treatments — his wife, Anita, their six children from their blended family, and 12 grandchildren supported him and helped keep his spirits up.

Second primary cancers

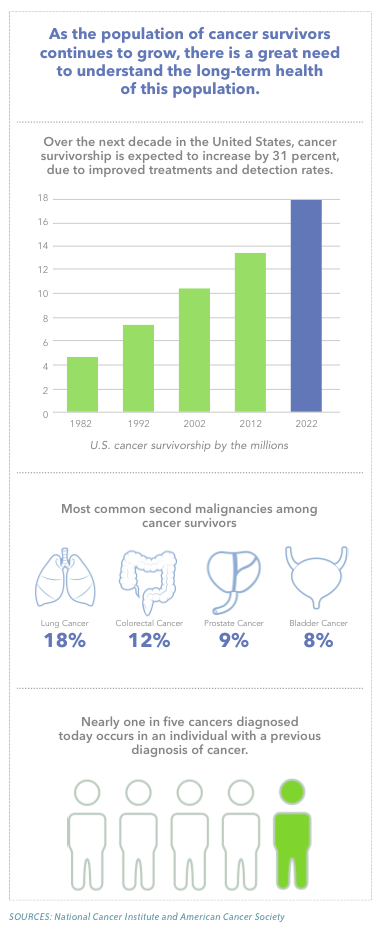

Nearly one in five cancers diagnosed today occurs in an individual with a previous diagnosis of cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI). These second primary cancers are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among cancer survivors. This means that it is even more important for cancer survivors to be aware of the risk factors for second cancers and maintain good follow-up healthcare.

Reasons for secondary cancers fall into three categories, said Debra Friedman, MD, associate professor of Pediatrics and director of the Division of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

- Cancers related to the treatment of the first (primary) cancer

- Cancers linked to a known genetic predisposition syndrome

- Cancers likely by chance

“Second primary cancers are not all due to effects of treatment of the first cancer or known cancer genetics. With people living longer, some, just by random chance, will develop a second primary cancer,” she said.

Friedman, the E. Bronson Ingram Professor of Pediatric Oncology, said that when cancers occur in quick succession it’s important to determine whether the second cancer is indeed a secondary cancer or a metastatic spread of the first.

“The shorter the latency period between the first and second cancer, the more concerned we are that it’s a recurrence or a metastatic spread of the primary cancer,” Friedman said.

To make that determination, physicians look at the histology (examine the cancer tissue under the microscope), the genetics of the cancers, and the location — does it make sense biologically that a second cancer could have spread from the location of the first cancer?

To make that determination, physicians look at the histology (examine the cancer tissue under the microscope), the genetics of the cancers, and the location — does it make sense biologically that a second cancer could have spread from the location of the first cancer?

“All the pieces come together and can say ‘this is a second primary cancer versus a recurrence of the first cancer’ or ‘this is a metastatic occurrence of the first cancer,’” Friedman said. “Someone can have a second cancer that’s grossly the same type as the first cancer (two leukemias, for instance) but the new one is slightly different. You have to be careful and know for sure if it’s a recurrence or a second type because you’ll treat them very differently.”

John Thomas, 79, of Somerset, Kentucky, battled two cancers within the same year. He was diagnosed with stage IV bladder cancer in September 2016. He had 12 rounds of chemotherapy, then surgery to remove his bladder. He had been urinating blood since 2014, but the cancer wasn’t found by his medical team in Kentucky.

Months after his first treatment ended, a Vanderbilt pathologist discovered a second primary cancer in his prostate. Thomas’ treatment plan included radiation and medication.

“When you are told you have cancer, it’s hard to take,” said Thomas, the father of three daughters. His wife died in 2013. “I cried (when he was diagnosed with his first cancer); I enjoy life so much. I fish a lot on Lake Cumberland. I love to be outdoors. My mother lived to be 105. I had to deal with thinking that my life might be over,” he said.

“But the second time, with the spot on my prostate, it didn’t even bother me. I was alright after the bladder cancer and I was just so happy I could be treated. I have a wonderful outlook on life. I told Dr. (Sally) York (his Vanderbilt oncologist) ‘when I get up in the morning, if I just take two steps out of the bed, I know I’ve got it made.’ The operations and the chemos, that’s all over. It’s a journey I had to take, and I’m all right with it.”

Treatment-related second cancers

The majority of cancer treatments today, despite significant advances over the past decades, still include agents that will alter DNA, agents that rapidly kill dividing cancer cells, Friedman said. “Obviously, you’re trying to treat the cancer with something that’s going to target the tumor and not damage tissue elsewhere. But the majority of cancer treatment still includes cytotoxic therapies (chemotherapy and radiation). However, this is changing, and currently for a number of adult-onset cancers, there are options for treatment targeted to the tumor, based on tumor genetics,” she said.

There have also been advances in immunotherapy, where the patient’s own immune system is used to kill the cancer. These therapies are still new, so the long-term risks remain largely unknown. “We believe they will be associated with a decreased risk of second cancers from the therapy itself,” Friedman said.

Some chemotherapy drugs are believed to increase the risk of second cancers, most commonly leukemia.

Chemotherapy agents believed to be linked to secondary cancers, mostly secondary leukemias and myelodysplastic syndrome, include etoposide, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and ifosamide. Chemotherapy is known to be a greater risk factor than radiation therapy in developing another cancer, she said.

Friedman said the time between the first cancer treatment and development of the second primary cancer can be short (within a year) or very long (20-plus years). Chemotherapy-related second cancers tend to occur earlier, and radiation-associated second cancers tend to occur later.

But physicians need to consider the timing, she said. If someone is treated for a tumor in the chest area and 10-15 years later is diagnosed with breast cancer, physicians tend to believe that’s associated. “But if they get radiation at 16 and breast cancer at 80, it’s unlikely to be related,” Friedman said.

Radiation therapy is also believed to increase the risk for solid organ tumors, both benign and malignant, when organs are in the original fields of radiation. For survivors of childhood cancer, radiation therapy is the most important risk factor for second cancers. But in general, the risk of having a second cancer from radiation is very low, and much depends on the amount of radiation given during treatment. The higher the dose of radiation received, the higher the risk for developing a second cancer.

“With advances, we’re trying to limit the exposure of normal tissue, but that’s not 100 percent possible yet in 2018,” she said.

Friedman said current research is focused on how to limit radiation exposure. “As we develop new treatment protocols for cancer, our goals are to limit exposure to the drugs that are associated with secondary leukemias and to limit the field dose of radiation and exposure to normal tissue, therefore limiting second cancers.

“But for now, if this is the very best therapy we have, and if it’s going to afford our patients a 90 percent chance of cure compared to a 5 percent lifetime risk of a second cancer, I’m not going to tell a patient I won’t give them this drug because of a small chance of a second cancer down the road, even if there is a lifetime risk. We always have to weigh risks and benefits.”

Understanding what is different between patients who develop a second cancer and those who don’t, related to their chemotherapy or radiation therapy for their first cancer, would provide many answers, she said.

“Ongoing research is underway to understand genetic risk factors, such as variations in genes that help break down chemotherapy or repair damage to DNA from chemotherapy or radiation therapy,” she said. But until it can be determined who is truly at the highest risk, there are some screening recommendations for secondary cancers, Friedman said.

Women who receive radiation to the chest for Hodgkin lymphoma, for example, are at increased risk of breast cancer and should undergo screening with mammography and breast MRI.

Genetic predisposition

There are genetic disorders that increase your risk for cancer for both primary and secondary cancers.

“If you have an inherited predisposition to cancer, generally, you are going to be at a much higher risk for multiple cancers in your lifetime,” said Tuya Pal, MD, clinical geneticist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and associate director for Cancer Health Disparities at VICC.

“If you develop a cancer, the chance you’ll develop another one in your lifetime is going to be much higher if you have an inherited predisposition compared to people in the general population,” Pal said.

When cancer runs in the family, survivors have a higher chance of developing second cancers than those who get cancer by chance. Survivors from families who have an inherited cancer predisposition should know their family history. They should also participate in specific follow-up care based on the inherited cancer predisposition running in their family.

If a genetic predisposition is found, there are cancer screening recommendations or preventive surgeries that may be appropriate, Pal said. The way that a primary cancer is treated may also differ if there’s a genetic predisposition that’s going to increase risk for a second cancer.

For example, a woman’s lifetime risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer is greatly increased if she inherits a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene.

Those women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations have a high risk of developing a second primary cancer in the opposite breast after the first breast cancer diagnosis, especially those diagnosed with their first breast cancer at an early age. It’s estimated that by 20 years after a first breast cancer diagnosis, about 40 percent of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation and about 26 percent of women who inherit a BRCA2 mutation will develop cancer in the other breast. These genes are also linked to a higher risk for developing ovarian cancer. Most ovarian cancers are detected when they have spread beyond the ovary, and there is currently no reliable method for detecting this type of cancer early. Consequently, many women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation decide to have their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed, which lowers the risk to develop ovarian cancer by over 90 percent.

“Once you’re identified to have a mutation, this gives you the opportunity to be proactive about your health. We can tell you, ‘these are the health issues you’re at risk for. Here are some targeted cancer risk management options we can provide you in order to keep you healthy,’” Pal said.

For example, if a woman is identified with a BRCA mutation, she should be getting high-risk screenings — annual mammograms and breast MRIs — and some women consider bilateral mastectomy to reduce their risk. For ovarian cancer management, if a woman is finished having children, it’s recommended that the ovaries and fallopian tubes be removed, because ovarian cancer is usually not detected early.

In the active breast and ovarian cancer treatment setting, identifying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation may change the treatment that doctors recommend for you, Pal said, adding that the cost of genetic testing has plummeted over the past decade. What used to cost thousands now costs hundreds of dollars.

But with increased numbers of people wanting testing comes a greater responsibility of the healthcare workforce, she said. “If

we offer broader scale testing, we need to have support services for these individuals — someone to explain what to do once you receive this information. Test results are not always straightforward. The workforce needs to be trained to interpret the results so that people don’t get overtreated or undertreated. The whole point to testing is to give a person what he or she needs to make appropriate medical management decisions based on family history and test results.”

VICC offers a clinic for people who want to be evaluated for hereditary cancer risk. The Vanderbilt Hereditary Cancer Clinic is staffed by several credentialed genetics specialists, including two physicians, two nurse practitioners and three genetic counselors. Providers can refer their patients, or patients can refer themselves by calling 615-343-7400 or by submitting the referral/request for an appointment directly via the website, go to www.vicc.org/hcp.

Second cancers by chance

Patients who have had cancer may, many years later, get another cancer. “This is probably just by chance because they have lived long enough to have developed an adult onset cancer,” Friedman said. “There’s the big unknown — is there something still with the genetics of that person that puts them at risk to develop a tumor when they’re 5 and again when they’re 90? Possibly. But we don’t know what that is.”

Lifestyle can be involved in all three scenarios, Friedman said. For example, a patient treated for Hodgkin lymphoma will most likely get radiation to the chest, and the lungs will be exposed to part of that radiation. But the incidence of a secondary lung cancer is only increased in patients who get both a significant dose of radiation and who smoke. “That’s where lifestyle plays a factor,” Friedman said.

The healthcare team should discuss with patients treated for cancer the importance of maintaining a healthy lifestyle and abstaining from behaviors that are known to increase the risk of cancer, like smoking. “Or if you currently smoke, we need to work on quitting. We know that smoking is associated with multiple types of cancer,” Friedman said.

Patients who have had radiation should also be even more diligent than the general population about sun protection and limiting sun exposure.

“And last, nobody has really looked at how a healthy diet decreases your chances of a second cancer, but it certainly can’t hurt,” Friedman said. “Lifestyle can affect all three of the categories, so let’s do what we can to mitigate the risk.”

Treating second cancers

Friedman said that some second cancers are harder to treat for a variety of reasons — genetically, they’re very complex or can be highly aggressive; and patients have already had chemotherapy and radiation and the cancer team can be limited as to what they can give. However, this differs significantly by case.

“Secondary leukemia and secondary myelodysplastic syndrome are very hard to treat, compared to primary leukemia or primary myelodysplastic syndrome. The survival rates are much lower. Secondary breast cancers, in contrast, may not be necessarily harder to treat than a primary breast cancer,” she said.

The emotional and psychological needs of patients should also be considered with a treatment plan.

“Some people exhibit great resilience — ‘It’s OK. I’ve been here before. I’ve fought it before. I won and I’m going to win again.’ These people come at it from a position of strength and actually grow psychologically from the experience,” Friedman said. “They have gained a new perspective on life and they’re not going to sweat the small stuff.

“And then there’s the group who have significant psychological dysfunction after being diagnosed with a second cancer — these are people who approach it as ‘It’s not fair, I can’t do this. I’ve been through this once.’ They have a certain amount of posttraumatic stress disorder and flashbacks of going through chemotherapy.”

VICC has nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers who help patients address these challenges.

For Thomas Brewer, maintaining an upbeat attitude helped him persevere. Since completing chemotherapy in February, he has walked daily for exercise, played gigs with his band and made a point to keep busy.

“A positive outlook is the greatest medicine against cancer,” he said. “I’m livin’ life. That’s what I did then (with the first cancer) and that’s what I’m doing now.”