The Mentor

November 22, 2017 | Bill Snyder

During a career that spans more than half a century, Harold “Hal” Moses, M.D., pioneered an entirely new research field aimed at suppressing tumor growth and helped build Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) into one of the nation’s leading cancer centers.

Moses, who will turn 80 in February 2018, has closed his lab and retired to emeritus status after 31 years as a Vanderbilt University faculty member, but he’s got a few things left to do before he packs up his office.

One of the items on his “to-do” list is to help secure funding for a program launched this summer at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) to increase the number of underrepresented minorities and disadvantaged students in medical school.

The “short-pipeline program” provides summer research experiences and biology and chemistry enrichment classes at Vanderbilt for undergraduate students from three historically black colleges: Morehouse and Spelman in Atlanta and Nashville’s Fisk University, and from Berea College in Berea, Kentucky—Moses’ alma mater.

As he puts it, “There are bright people out there of all types.”

Moses should know. Disadvantaged is where he started. He and his older brother Ray grew up in a house without running water on a hardscrabble farm in southeastern Kentucky. Neither of his parents graduated from high school. His father was a coal miner.

Moses learned to plow with horses. He was going to stay on the farm until a doctor in a little coal-mining town suggested medicine instead. He followed the doctor’s advice. He worked his way through college and earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Berea College in 1958. He applied to three medical schools. All accepted him. He chose Vanderbilt.

Four years later, at age 24, he graduated in the top 10 percent of his class. On the day he received his diploma, his father died of black lung disease at age 60.

It was at Vanderbilt that he met his future wife, Linda. In August, they celebrated their 55th wedding anniversary.

Jekyll and Hyde

In 1965 Moses accepted a Public Health Service commission. He set up his first lab in experimental pathology at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and three years later was offered an assistant professorship at Vanderbilt. Then in 1973, he accepted an associate professorship at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where he made one of the most pivotal discoveries of his career.

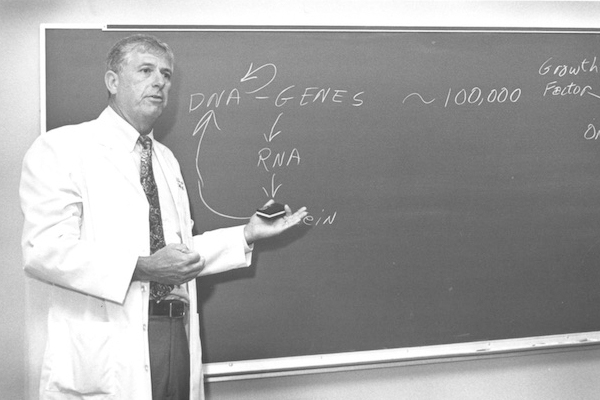

In the early 1980s, Moses and his colleagues at Mayo first described and purified a “transforming growth factor” (TGF-beta) that could stimulate cell growth and in some cases aid metastasis, the spread of cancer cells to distant parts of the body. Remarkably, the protein could also inhibit normal cell growth. Moses dubbed the protein the “Jekyll and Hyde of cancer.”

The discovery of TGF-beta’s inhibitory capacity “opened the doors to the study of growth factors as negative growth regulators,” notes longtime colleague Jennifer Pietenpol, Ph.D., current VICC director and Executive Vice President for Research at VUMC. It was a “paradigm shift at the time,” said Pietenpol, Benjamin F. Byrd Jr. Professor of Oncology.

Moses returned to Vanderbilt in 1985 to be the chair of Cell Biology. In 1993, he was asked to head the newly established Vanderbilt Cancer Center. He accepted the job despite feeling apprehensive about its fundraising responsibilities.

“I didn’t think I would enjoy that,” he said. “But I did. You get to meet a lot of very smart people who want to invest their funds in something worthwhile, and you give them the opportunity.”

World without Cancer

In his new role, Moses worked with Peggy Joyce. She and with her mother, Kathryn Craig Henry, made a gift in 1986 to create the Henry-Joyce Cancer Clinic in memory of Peggy’s husband, Harry Joyce.

Joyce recalled with humor how Moses talked too much like a scientist when he started as cancer center director.

“With a little tutoring from (board member) Frances Preston, he learned to explain things that went on in the laboratory in layman’s language where we thought we could understand it,” Joyce said.

At the time, Preston was CEO of the music licensing company Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI) and chair of the T.J. Martell Foundation for Leukemia, Cancer and AIDS Research, the music industry’s leading charity.

At the time, Preston was CEO of the music licensing company Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI) and chair of the T.J. Martell Foundation for Leukemia, Cancer and AIDS Research, the music industry’s leading charity.

In 1992 the Martell Foundation established a research lab at Vanderbilt in her name. Moses directed the lab for more than 20 years.

In 1995 prominent Nashville industrialist and former chair of the Vanderbilt University Board of Trust E. Bronson Ingram died of cancer. About two years later his son, Orrin Ingram, was sitting in Moses’ office talking about the Vanderbilt Cancer Center.

“I felt helpless at not being able to save my father,” said Ingram, CEO of Ingram Industries, chair of the VICC Board of Overseers and a former member of the Vanderbilt University Board of Trust. “Hal helped me understand how I could launch my frustration into helping other people.”

Ingram asked what it would take to build the Vanderbilt Cancer Center into one of the best in the country. A few weeks later, Moses came back to him with a vision that would require $56 million in the first five years and $94 million in the following five years. In 1999, the Ingram family pledged to provide the first $56 million for the center, which was renamed the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) to honor Bronson Ingram. Orrin Ingram led a national campaign called Imagine a World Without Cancer to raise the balance. The final tally exceeded $180 million.

“It’s the best investment I’ve ever made in my entire life,” Ingram said. “Hal took a dream and he’s made it more and more a reality. We’re not all the way there yet but we’re a lot further down the road than we were when we started. I feel so much passion about this guy. He’s truly amazing.”

“It’s the best investment I’ve ever made in my entire life,” Ingram said. “Hal took a dream and he’s made it more and more a reality. We’re not all the way there yet but we’re a lot further down the road than we were when we started. I feel so much passion about this guy. He’s truly amazing.”

Moses recruited other philanthropic entities to support VICC, while expanding its research initiatives. A primary goal was to achieve the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) highest designation as a comprehensive cancer center, which required a strong epidemiology program. Under Moses’ leadership, Vanderbilt recruited internationally known epidemiologists and partnered in development of one of the nation’s largest population health studies. VICC achieved top NCI designation in 2001. It has maintained the top designation through three subsequent rounds of intensive external reviews.

In 2005, Moses handed over the reins of the VICC to Raymond DuBois, M.D., Ph.D. The move gave Moses more time to focus on his research. Over the years, he’s served as president of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and Association of American Cancer Institutes, co-chair of the NCI Progress Review Group and chair of the NCI Cancer Centers review panel. He remains principal investigator of a research partnership on cancer disparities with Meharry Medical College and Tennessee State University that has been funded continuously by the NIH since 1999.

“Hal’s legacy is remarkable,” said DuBois, current dean of the College of Medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina. “He diligently and deliberately recruited an outstanding faculty of researchers, clinicians and translational practitioners to promote (the cancer center’s) expansion.”

Moses also recognized early “the long-term advantages of involving the country music industry, local business leaders and the community at large to help cancer patients and their families,” DuBois continued.

Moses worked closely with Lawrence “Larry” Marnett, Ph.D., dean of Basic Sciences and Mary Geddes Stahlman Professor of Cancer Research.

“Hal just had a really great sense of vision, not only establishing a vision with the input of a lot of the senior leadership, but sticking to that vision,” Marnett said.

Carry the torch

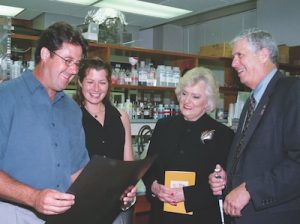

Moses takes great pride in the graduate students and research fellows who trained in his lab over the years, including Pietenpol.

“I had the great fortune of first working with Hal in the mid-1980s, first as an undergraduate and subsequently as a graduate student,” Pietenpol said. “Hal is a wonderful mentor who really cares about the people who work with him, and he always has the best interests of people at heart.”

“I had the great fortune of first working with Hal in the mid-1980s, first as an undergraduate and subsequently as a graduate student,” Pietenpol said. “Hal is a wonderful mentor who really cares about the people who work with him, and he always has the best interests of people at heart.”

Moses met Pietenpol at his daughter Jill’s birthday party in Rochester, Minnesota, in the summer of 1982. She was a classmate of Jill’s at Carleton College.

Pietenpol asked Moses if he could help her find a summer job at the Mayo Clinic. The next summer he did—in cardiology. After her junior year, she transferred to his lab. And then Moses was recruited back to Vanderbilt. Pietenpol followed Moses to Vanderbilt for graduate school and then as a VICC cancer researcher.

After DuBois left Vanderbilt in 2007 for a leadership role at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Pietenpol became the center’s third director.

Ingram applauds the decision. “Any great leader is truly great when they can replace themselves with somebody who’s as good or better,” he said. “One thing she does better—she’s a fabulous salesperson as well as a visionary and implementer. So (Moses) mentored somebody to carry the torch and that’s huge.”

Moses has received numerous honors: election to the National Academy of Medicine; the Earl Sutherland Prize, Vanderbilt University’s top research award; the T.J. Martell Foundation Lifetime Achievement Medical Research Award; the AACR Award for Lifetime Achievement in Cancer Research.

“Harold Moses has spent his entire career decoding the secrets of cancer cells, training the next generation to share his passion for research, and building frameworks to support biomedical research, both locally and nationally,” Pietenpol said. “The fundamental discoveries that have resulted from his efforts and those of his laboratory teams have served as the building blocks for entire areas of cancer research.”

In honor of his contributions as a scientist, leader and mentor, friends and colleagues have established the Linda and Harold L. Moses, M.D., Career Development Fund at VICC.

A new beginning

Moses’ commitment to increase the number of underrepresented minorities and disadvantaged students who go to medical school is another way of giving back.

Asked for his prediction about the future of cancer research and treatment, Moses just smiled.

“I didn’t see the revolution in genomic medicine and targeted therapies coming,” he said. “I certainly did not see the breakthrough in immunotherapy … or genome editing coming along.”

To prepare for the unknown, he said, “You’ve got to have people with a variety of talents.”

1 Comment

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Hal, I’m delighted to see the nice long article about you and your accomplishments at VU. Each time I enter the building I see the marvelous big picture of you. Time has passed quickly from the days of Dr. Shapiro’s pathology intern/ residency programs and obviously you have taken advantage of every opportunity to grow and serve. Congratulations and best wishes to you and your family. Lee Penuel

Comment by Lee Penuel — December 16, 2017 @ 9:56 pm