Spotlight on Cancer: Lung Cancer

Decision Precision

January 28, 2016 | Tom Wilemon

Photo by Daniel Dubois

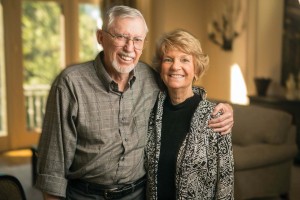

After two years of worrying about a nodule in her lung, Emmy Edwards said yes to surgery.

She could have flipped a coin had the stakes been smaller.

A nonsmoker, Edwards had been more worried about heart disease than lung cancer when the tiny lesions showed up during a cardiac CT scan. They were in a part of her lungs where they couldn’t be biopsied with a needle.

“I had a 51 percent chance that those nodules were not cancer, so a 49 percent chance they were,” she said. “To me, those are not very good odds.”

A team at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) spent two years evaluating her case—a process that involved advanced imaging, probability analysis and a lot of medical pondering.

Edwards, a healthy and active woman in her 70s who played tennis regularly, personified a quandary within cancer research and treatment—the debate about early intervention vs. overtreatment.

Doctors didn’t know for certain she had lung cancer until she underwent surgery on Aug. 28, 2015. They’re still not certain how much risk the malignancy posed, but Edwards is helping them solve that mystery.

Her nodules were discovered in 2013, the same year that a working group sanctioned by the National Cancer Institute raised concerns about overdiagnosis and overtreatment. The group noted that some cancers are “indolent disease that cause no harm during the patient’s lifetime” in an editorial published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), but they identified only a few of those lazy cancers.

“Molecular diagnostic tools that identify indolent or low-risk lesions need to be adopted and validated,” they wrote.

VICC researchers have answered that call.

One of them is Pierre Massion, M.D., Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Medicine, who kept watch over Edwards. A scientist who specializes in lung cancer, he’s identified effective strategies for early detection and is involved in several research initiatives to better understand the progression of the disease. His investigations include delving into how oncogenes progress to tumors and pinpointing the molecular biomarkers for malignancies.

With Edwards, he had to rely on imaging. The first nodule, which had been discovered in her left lung during the cardiac scan, wasn’t indicative of cancer. But a second one, found in her right lung during a follow-up chest CT, was suspicious.

“Three months later, I was worried about this,” Massion said.

“I told her this may very much be a cancer although she was a never smoker. We kept following her over another six months. Then another six months.”

Edwards and her husband, Frank, would drive two hours to Vanderbilt from Crossville, Tennessee, for multiple appointments during the period of watchful waiting.

The nodule in the upper lobe of her right lung started to change in 2014.

Advanced diagnostic tools at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Radiology showed that the solid portion of the nodule was growing—something that would not have been immediately apparent with less intensive screening technology. Ronald C. Walker, M.D., alerted Massion and provided him with images from multiple perspectives, and information about the importance of its density.

“To the non-expert, this nodule is nothing to worry about,” Massion said. “But to the expert, when the solid component of the nodule grows, this may signify cancer.”

He noticed that the solid portion of the nodule had grown by 61 percent, which is usually a signature of cancer. But he still could not definitively determine whether it was benign or malignant.

Although Massion has devoted 17 years to lung cancer research and is an expert other scientists seek out for advice, he wanted other opinions. He brought Edwards’ case before a panel of experts at VICC’s tumor board that included a radiologist, oncologist, pathologist, surgeon, pulmonologist, radiation therapist and statisticians who work in cancer modeling.

The panel included Eric L. Grogan, M.D., a thoracic surgeon, who has worked with Stephen Deppen, Ph.D., an epidemiologist, in using a surgery determination formula called the TREAT model developed at VICC with support from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

“We have developed a tool that allows us to go to a website and pull up a calculator that shows the patient what the probability is of whether a lesion is cancer or not,” Grogan said.

The two wrote an article about their risk model for lung nodule classifications published in the Spring 2015 issue of Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. Noting that Medicare and private insurers had in February 2015 begun covering CT scans for people who are at high risk for lung cancer, they estimated that 3.1 million lung anomalies will be discovered within the first three years of expanded coverage—setting up the scenario for thousands of unnecessary diagnostic surgeries.

While other models have been developed, their study showed that TREAT had better diagnostic accuracy. However, there were too many gray areas with Edwards for the formula to be definitive.

She didn’t want to flip a coin on cancer.

Edwards talked it over with her family and decided it was best to have the surgery as a healthy 75-year-old instead of potentially having to undergo the operation in later years when the nodule—possibly by that time cancerous tumors—had spread.

“We decided let’s go ahead and have it out because you never know what the catalyst is that will make these decide to grow and be more dominant,” Edwards said.

In the operating room, Grogan worked with an interventional pulmonologist, Otis B. Rickman, D.O., who marked the lesion. The marking of the tumor helped Grogan perform a minimally invasive surgery.

The pathology team informed the surgery team while still in the operating room that the nodule was cancer—adenocarcinoma. The surgical team removed the upper lobe of her lung and lymph nodes through the same incisions while she was still under anesthesia. When the procedure was over, her biggest incision was less than an inch long.

The final pathology report revealed Stage 1 lung cancer. Edwards is in remission.

“The remarkable thing about this lady and her clinical care— and I’m not even talking about the research piece here—is really the amount of expertise she was able to garner from our institution,” Grogan said. “I think that’s a very important message. When Pierre (Massion) has someone that he is concerned about, (that patient) is not just going to get one person’s opinion.

“He brings (the patient’s case) to the tumor board. The radiologists do special models to determine that the lesion has grown. Interventional pulmonologists help to localize the lesion so that a minimally invasive operation can be performed. In the end, patients receive state-of-the-art, personalized care because of a comprehensive skilled team that comes together at the right time.”

Edwards donated her tumor and lung tissue to VICC for research. Although adenocarcinoma is a very common type of cancer, every tumor is different. Each one is made up of different mutations and genetic characteristics.

Massion was awarded National Cancer Institute funding in March 2015 to decipher the molecular processes that spur invasive actions in lung adenocarcinoma. He’s one of two primary investigators of a multi-institutional effort to understand the biology of these early tumors, identify biomarkers for this type of cancer and stratify the degree of risk they pose. A first step is increasing tumor donations for adenocarcinoma repositories.

He’s also the principal investigator of two other NCI-funded initiatives. One is to develop a prediction model to help physicians determine the best intervention for lung adenocarcinoma—surgery, chemotherapy or adjuvant immunotherapy—based upon a genomic molecular test. The other initiative is research to better distinguish between benign and malignant nodules discovered during CT screenings.

Edwards said the knowledge that she was promoting cancer research through the donation of the tumor made her feel less like a cancer statistic.

“This is her tissue,” Massion said, pointing to a screen where portions of the tumor had been color-coded. “The different areas of the tumor mean that she may have different types of clonal populations in these little squares.”

The cells within a tumor can have distinct differences in gene expression, growth patterns and metastatic potential. Massion explained how this heterogeneity in Edwards’ tumor was dominated by cells identified in blue that might respond well to one type of chemotherapy only to have the pink cells spur into action.

“That’s a nightmare for the oncologist,” he said.

When cancer cells mutate or when a different clonal population becomes dominant, chemotherapy often stops working.

Frank and Emmy Edwards look forward to their next road trip. They had just driven their van from Alaska back home to Tennessee in 2013 when her lung nodules were discovered. Photo by Daniel Dubois.

Edwards’ cancer was caught early enough that chemotherapy was not prescribed. She said doctors did not pressure her into undergoing surgery. With two graduate degrees and the experience of having run a successful business, she had the education and experience to make the call. She also had the support of her husband, a retired university professor, to give the decision a logical analysis.

As scientists like Massion discover ways to better analyze the real risks posted when nodules pop up in CT scans, surgeons like Grogan will also need better tools to explain that information to patients. Grogan said that while he’s pleased with how the TREAT model has worked, he sees areas for improvement.

“Patient reaction to this information is varied, and the shared decision making that is going on with the management of pulmonary nodules is very complex,” he said.

One problem is how does a doctor help a patient factor out emotional responses, Grogan said, raising the scenario of someone saying no to surgery because a family member may have died from a surgical complication. Physicians also have life experiences that play into decision-making.

Grogan is partnering with a human factors expert, Matthew Weinger, M.D., Norman Ty Smith Professor of Patient Safety and Medical Simulation, on seeking a follow-up VA grant to look at how the TREAT model impacts physicians’ recommendations to patients with pulmonary nodules. They also want to study its effect on the decisions made by those patients.

A month after her surgery, Edwards was doing mile-and-a-half brisk walks with her husband near their Crossville home on the Cumberland Plateau. She said she’s looking forward to getting back on the tennis court and traveling again.

“I really, really truly feel blessed because we were able to discover this thing so early,” Edwards said. “Now, the prognosis is very positive.”