Keeping Up With Cancer

Hematology/Oncology fellowship program working to fill need for future oncologists

June 22, 2011 | Nancy Humphrey

The long-term forecast for the fight against cancer is indeed gloomy if a predicted shortage of oncologists comes to pass.

The impending shortage, predicted recently by a study commissioned by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), could result in a shortage of as many as 4,000 oncologists by 2020, causing cancer patients to travel longer distances to be seen, and wait longer for an appointment, both of which could affect outcomes.

“If the shortage isn’t corrected people will have to wait for cancer care,” said Jill Gilbert, M.D., associate professor of Medicine, who directs Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center’s Hematology/Oncology fellowship program, one of the largest academic medical center-based programs to train the next generation of oncologists.

“This could affect timely appointments. Patients may also have to travel longer distances because there will be some communities where medical hematology/oncology services may not exist. That’s a big deal when you’re a patient with limited funds, limited energy and limited resources.”

Vanderbilt-Ingram recently got the green light to increase the size of the three-year hematology/oncology fellowship program from 18 to 21 fellows, and other cancer centers are trying to grow their programs as well, but one roadblock still remains – how to pay for these costly, critical programs.

It costs $80,000 a year to train a fellow, Gilbert said. “So you’re talking about almost a quarter of a million dollars over three years, including benefits. In this era of a difficult economy and shrinking health care dollars, who’s going to take the burden? Who’s going to pay for it?”

Why a shortage?

The cause of the predicted shortage is twofold – more cancer patients and fewer oncologists to treat them.

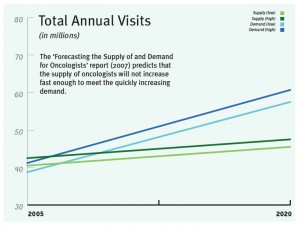

The ASCO study, conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges Center for Workforce Studies, predicts a significant increase in patients who will need an oncologist by 2020 – driven by the rising incidence of cancer with age (especially after age 65) and a growing number of cancer survivors due to improvements in screening and treatment. Using Medicare data to estimate, the study predicts a 48 percent increase in cancer incidence and an 81 percent increase in people living with or surviving cancer between 2000 and 2020.

At the same time, the supply of oncologists needed to treat those patients is not expected to increase fast enough for the demand – because of the disproportionate number of oncologists nearing retirement and the limited number of oncology fellowship slots.

What’s a fellow, anyway?

To become a practicing specialized oncologist, a physician must be properly trained, and that’s where fellowship programs, like Vanderbilt-Ingram’s, come into play. A fellowship is a period of medical training that a physician undertakes after completing a residency, a time to become more focused on the specialty or subspecialty he or she has chosen.

Vanderbilt’s Heme/Onc Fellowship program is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and is approved to train six fellows per year in a combined hematology/oncology training program. The fellowship is divided into 18 months of clinical time and 18 months of mentored research. Most of Vanderbilt’s fellows seek both hematology and oncology board eligibility, but some prefer to focus on one track. The program is flexible so that the fellows can tailor the three years to best suit their career choice.

Fellowship program director Jill Gilbert, M.D., (right), attributes the success of Vanderbilt’s program to the variety of clinical and research opportunities available. (Photo by Susan Urmy)

Prior to 1997, hematology and oncology were independent academic divisions with each division maintaining a separate fellowship program. In 1997, the two divisions were merged, partly to enhance training opportunities for fellows. They are given research opportunities in clinical investigation, molecular biology, cellular biology, genetics, signal transduction and pharmacology.

The number of applications to Vanderbilt’s fellowship program has continued to rise with 323 applications submitted and 49 interviewed for the six fellowship slots that began in 2010.

In addition to the straight fellowship program there are also two complementary NIH-funded training grants that Vanderbilt fellows may obtain after their fellowship – a K12 entitled “Vanderbilt Clinical Oncology Research Career Development Program,” designed for physicians interested in a clinical oncology research career with an emphasis in an academic-oriented environment, and a T32 entitled “Vanderbilt Training Program in Academic Cancer Research.” Unlike the K12, the T32 program is designed exclusively for adult hematology/oncology fellows seeking training in laboratory or patient-oriented translational research. Two T-32 fellows are funded each year, on a competitive basis.

Gilbert said that Vanderbilt’s program turns out exceptional fellows because of two specific reasons: the variety of the clinical experience and the strength of the research opportunity. Fellows are exposed to patients in multiple venues (Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, the underserved population of Meharry Medical College, as well as the generally male population with tobacco-related diseases at the Veteran’s Administration Medical Center), and the research experience includes opportunities in clinical investigation, translational and bench research, and the Personalized Cancer Initiative, which personalizes treatment by matching the appropriate therapy to the genetic changes, or mutations, that are driving the cancer’s growth.

Many graduates of Vanderbilt’s fellowship program have gone on to highly successful academic research careers at Vanderbilt and other institutions like MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas Southwestern, Moffitt Cancer Center and Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo. Others are leaders in community practices throughout the country.

Melding together

Christine Lovly, M.D., Ph.D., a third-year fellow has chosen to tailor her fellowship to Vanderbilt’s lung cancer program so that she will be coordinating patient care with research. She plans to practice in an academic setting and her research focus is currently in the lab of William Pao, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of Hematology and Oncology and director of the Personalized Cancer Medicine Initiative. She recently received a $100,000 grant from the nonprofit Uniting Against Lung Cancer Foundation to study better treatment options for a subset of lung cancer patents harboring specific genomic alterations in the ALK gene.

Third-year fellow Christine Lovly, M.D., Ph.D., (left) is tailoring her fellowship to coordinate patient care with research. (Photo by Susan Urmy)

“My research focuses on trying to understand how the ALK gene works in lung cancer, and what are the partners of ALK in lung cancer,” she said. The timing of the research is crucial since the first drug to inhibit ALK, crizotinib, has shown great promise.

“We know for these targeted therapies that patients will respond and have dramatic responses, but eventually their disease will come back. One of my major interests in trying to figure out how cells overcome this ALK inhibitor.”

Lovly, who will a complete four years of oncology fellowship in order to continue her research efforts, said she appreciates the program’s flexibility. She knew early on that she wanted to focus specifically on one disease site (lung).

“This program really let me tailor what I wanted to do for my career. I was able to say ‘here’s what I want to do; help me accomplish my goals.’”

Lovly said both the clinical and research aspects of her fellowship are rewarding. “Holding a patient’s hand, when he or she is talking about feeling bad, is very gratifying. Science takes a little longer. It’s a different type of gratification, equally wonderful, but just different. One of the best things about what I do here is that I treat patients with the ALK mutation in my clinic, and then I go study their disease on a molecular level in the lab. “There aren’t a lot of people who have had the opportunities I have had in both the clinic and the lab, and I’m very grateful for my experiences in both arenas.”

Going home

Vanderbilt’s program also turns out clinicians who will practice community oncology. Cynthia Shepherd, M.D., Vanderbilt’s chief Heme/Onc fellow, will be finishing her fellowship in June and returning to her hometown of Athens, Ga., to join an eight-physician oncology practice. She and her husband (and high-school sweetheart), Brad Shepherd, matched here for their residencies – her husband in gastrointestinal medicine – and after completing their fellowships, will return home with their two young children to practice medicine.

Find out where some former fellows are now -- and what they say about the Vanderbilt fellowship program. Click image to view slideshow.

“The good thing about this fellowship is that you feel comfortable in either clinical practice or doing research,” Shepherd said.

“Your last year, once you’ve made the decision about which way you’re going to go, each fellow tries to tailor the program to best suit his or her needs. I’ve been focusing more on doing a lot of clinic, because that’s what I’m going to be doing in the private practice setting.”

Shepherd said she is “well trained” to take care of a variety of oncology patients. “We see a lot of the common cancers, and we see uncommon cancers as well. We are trained on how to discuss clinical trials with patients so that they can make an educated decision and be willing participants. That has been very important to me since my practice will be doing clinical trials.”

Shepherd said she can’t imagine a better place to train. “What I’ve loved about this program is that everybody is so approachable and accessible. I hope to keep up these contacts when I’m settled into my practice in Georgia.”

Carol O'Hare is giving back to the institution that saved her life and fought to save her husband's by supporting the Hematology/Oncology Fellowship Program. Click to read her story.

What next?

The ASCO study said it will take more than one single action, like increasing the number of fellowship training slots, to divert the impending shortage. But several scenarios could shrink the gap. Other physicians or nurse practitioners could be trained to take over some aspects of cancer care, or different health care professionals could care for patients at different stages. Also, increasing the use of the electronic medical record, something that Vanderbilt already is a leader in, can improve efficiency in those already practicing oncology.

The impending shortage is on the minds of all newly-trained fellows, Shepherd and Lovly said.

“One in two men and one in three women in their lifetime will be diagnosed with cancer,” Lovly said. “Certainly, having people on all levels – physicians in private practice and those who can be at the forefront of new therapies – is very important. Not only do we need more oncologists, but we need people who are going to say ‘I’m going to study this particular disease and help find the best treatment for it that I can.’ We have a lot of cancer research in the United States, but we need more.

“A lot of our patients we can’t cure, and that’s what we want for them.”