Spotlight: MULTIPLE MYELOMA

The Waiting Game

ER doctor refuses to sit idly by waiting on disease to progress

December 8, 2010 | Leslie Hill

Bomar Herrin, M.D., never missed a workout. At 58, he was averaging 16 pull-ups, punching the speed bag and doing the grueling P90X exercise program. But during his regular weightlifting routine in July 2009, Herrin felt something snap near his right shoulder. Drawing on his 30-year career as an emergency medicine physician, he thought he had dislocated his shoulder and attempted to put it back into the socket himself.

When that didn’t work, Herrin went to the emergency room near his Johnson City, Tenn., home and was diagnosed with a pathological fracture – a break that occurs when the bone is diseased – near his shoulder in the humerus.

“I was never sick a day in my life and have never missed work, but now

I had this broken arm hanging loose waiting to be repaired,” said Herrin, a 1978 graduate of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “A lot of people are fond of saying they’ll give their right arm for something, but I encourage them to reconsider. It’s not an easy thing.”

Herrin was referred to Jennifer Halpern, M.D., assistant professor of Orthopaedics & Rehabilitation at the Vanderbilt Orthopaedic Institute, who surgically repaired his arm five days after the break.

Although the break was fixed, a biopsy revealed that it was caused by a solitary plasmacytoma, a cluster of cancerous plasma cells found in a single site, usually bone.

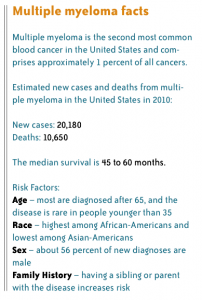

Plasma cells are a type of white blood cell that produces antibodies. When they become abnormal, the cells are called myeloma, and when myeloma cells collect in several areas of the body, the resulting disease is called

multiple myeloma.

But Herrin doesn’t have multiple myeloma – not yet.

Adetola Kassim, M.D., assistant professor of Medicine in the Division of Hematology/Oncology, says Herrin is in an early/precursor stage of the disease process, with solitary plasmacytoma and associated “monoclonal gammopathy.” It can take up to 30 years for some patients to progress to multiple myeloma.

“We know that patients who are diagnosed in these early stages of the disease will progress at the rate of about 1 percent per year to multiple myeloma,” Kassim said. “We really don’t treat patients [with chemotherapy] in the early phase; however, they need to be followed closely by their hematologist or local physician to monitor for signs of progression.”

Herrin had radiation to treat the plasmacytoma in his arm, and a PET scan revealed small lesions on his thoracic spine, sacrum and ribs. The scan indicated that the cancer may have spread, but wasn’t conclusive enough to warrant further treatment.

“I was back seeing patients the Monday after the surgery,” he said. “The radiation didn’t make me sick. This was primarily an orthopaedic injury, not the sickness people typically describe with cancer.”

But the waiting game had begun.

“Now we have to wonder how long the lesions will sit there. We can’t pretend they’re not there, but we don’t know what they mean. The best-case scenario is that everything just sits right where it is.

But you begin to wonder what you can do instead of just waiting.”

Once a patient does progress to multiple myeloma, standard course of treatment is chemotherapy followed by an autologous stem cell transplant (transplant of the patient’s own bone marrow stem cells).

“If we stop at chemotherapy, most patients relapse after nine to 15 months. However, with the addition of the stem cell transplant and possible maintenance therapy, we are able to keep them in remission for at least three to five years,” Kassim said.

Herrin’s stem cells have been harvested and stored in case he needs a stem cell transplant in the future.

“Using a patient’s own stem cells is best,” Kassim said. “Dr. Herrin had clean bone marrow, and being able to harvest and store his stem cells was like putting some money in the bank. If we tried to collect them later when his myeloma had progressed to a more systemic disease, his bone marrow would be more contaminated and may impact disease outcome.”

The biggest research question in multiple myeloma right now is what causes patients to progress from the precursor condition and solitary plasmacytoma to full-scale disease. Kassim is collaborating with the Vanderbilt Center for Bone Biology to study the bone marrow microenvironment for indicators that determine disease progression. There is also an effort under way to develop a collaborative myeloma initiative at Vanderbilt, comprising all the areas involved in multiple myeloma research and care – Hematology, Orthopaedics and Nephrology.

“By better understanding the intricacies of what happens within the bone marrow microenvironment and its association with these disordered plasma cells, the immune system, the bone itself and the different mechanisms by which all these are altered to facilitate myeloma progression, we can clearly direct targeted therapies to try to halt myeloma progression,” Kassim said.

Mia Levy, M.D., assistant professor of Biomedical Informatics and Medicine, is leading an effort to create a tissue repository for multiple myeloma specimens. By using informatics principles to manage the repository, research is faster and more organized.

Patients must give consent for their tissue to be banked in the repository, and it is not linked to their identity but is linked to their clinical information.

“We already have repositories for the common cancers, like lung, breast and colon cancer, and we’re starting one for head and neck cancer. Multiple myeloma is traditionally very rare and doesn’t have the same volume of cases or money devoted to it as more common cancers. This repository is important to help research in this so-called ‘orphan disease’ get off the ground,” Levy said.

Herrin made a philanthropic donation to build this repository because he is adamant about advancing multiple myeloma research.

“I don’t want my tissue just going in the biohazard trash bin after the biopsy that tells me it’s cancer. I want to know more than just that. I want them to learn as much as they can on the front end and move forward with research studies,” he said.

Herrin’s son, Pat (far right), pictured here with brother Ian and sister Grace, accompanied his father on one of his many visits to Vanderbilt. That trip led to Herrin’s gift in honor of Columbus Jones (see sidebar below). (Photo courtesy of Herrin family)

Herrin says people are willing to try unusual treatments after all the conventional ones have failed at the end-stage disease. But his experience with the disease so far, as well as what he has seen practicing emergency medicine, makes him want to stay as far from end-stage disease as possible.

“I’m not interested in a clinical trial at the end stage that only gets me three more months,” he said. “I’m interested in research on the front end. It’s the difference between three months so sick you can’t do anything or a year or two at the front end while you’re still able to do stuff.”

Herrin’s push for action is valid, Kassim said, but rigorous studies are needed to determine if the treatment is working or patients are just not progressing yet.

“Unfortunately, most of medicine is geared towards a reactive and treatment approach,” he said. “We need to invest some time and money into how we can halt disease progression in its tracks once it has been determined someone has a predisposition. But, we’ve not been able to show clinically that if I catch a patient in that interim phase that aggressively treating will stop the disease from progressing.

“Many patients, Dr. Herrin included, find it difficult to accept that all they have to do is wait for the disease to progress.”

“When you have an incurable disease, you do everything you can to fight it,” Herrin said. “You’re like, ‘Sign me up, where’s the dotted line?’ I have a lot of reasons to stay healthy.”

Those reasons include his wife Janice and children Ian, Pat and Grace.

Herrin is back to a modified exercise routine – using resistance bands instead of weights, and throwing a football, just not as far.

“I haven’t changed as much as I would have wished. I stop to smell the roses no better than ever,” he said. “I do get tired sooner than I used to and I’m tired of getting tired. I’m trying to do things I have always done but often frustrated that I can’t. And I don’t know what to blame things on – cancer or birthdays?”

For now, only time will tell.

***

Providing what’s needed

Columbus Jones shares a laugh with friend Dru Bratton-Newsom during a recent visit to Vanderbilt.

Bomar Herrin made one single stipulation on his $50,000 gift to the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center – that it be made in honor of Columbus Jones.

On one of his trips to Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Herrin was accompanied by his then 17-year-old son Pat.

“Pat was scared because he had never seen me that sick,” Herrin said.

While he was rolled away to X-ray, Jones – an electronic imaging tech at Vanderbilt – struck up a conversation with Pat and helped ease his worries.

“It seemed obvious that he ought to be acknowledged for his good work. Folks have no idea how valuable it is to me that he befriended Pat,” Herrin said.

Jones started at Vanderbilt in 1961 as a record assistant, then served as an electronic imaging tech from 1966 until his retirement in 2008.

“Patient care is just what we were about,” Jones explained. “I wanted to satisfy their needs and provide whatever they needed when they needed it. Why people come to us is for relief, and that’s all I knew to do.”

Jones said he was especially compassionate toward children because he has four daughters of his own.

Though he doesn’t specifically remember what he said to Pat that day, Jones said he was “blown over” when he heard about the gift in his honor.

“I was glad to know that what I did had meaning for somebody else, not just myself because the work I did was so enjoyable for me.”

Photo(s) By: Photos by Joe Howell