Thoroughbreds

In horse breeding and cancer research Hancock family aims to win

March 12, 2013 | Leigh MacMillan

Arthur Boyd “Bull” Hancock Jr. Photo courtesy of Keeneland-Meadors

Dell Hancock remembers the day 40 years ago that the idea for the A.B. Hancock Jr. Memorial Laboratory for Cancer Research at Vanderbilt took form. Her father, Arthur Boyd “Bull” Hancock Jr., had recently died from pancreatic cancer. The family planned for memorial donations to go to a national cancer foundation, but one particularly large donation gave her mother, Waddell Walker Hancock, pause.

“She put the check in her robe pocket and she said, ‘we can do something with this that will be better,’” Dell Hancock recalls.

Waddell Hancock, an alumna of Vanderbilt University, consulted with family friend F. Tremaine “Josh” Billings, M.D., Bull Hancock’s college roommate and a Vanderbilt physician.

“They came up with the idea of a lab,” Dell Hancock says. “Mama was hell-bent and determined to find out the cause of cancer, and that’s what they set out to do in the Hancock Lab.”

This year, as it celebrates its 40th anniversary, the Hancock Laboratory continues its focus on the causes of cancer – and on the development of novel agents for cancer imaging, prevention and treatment.

Bringing the best together

Bull Hancock was a third-generation horse breeder. He grew up at Claiborne Farm, the Paris, Ky. farm his father started in 1910 (his grandfather owned a breeding farm in Virginia).

Claiborne Farm is “the magic kingdom of Thoroughbred breeding,” according to Keeneland magazine, which covers the sport. More Triple Crown winners – six of the 11 – have been conceived at Claiborne Farm than at any other farm. The famed horse Secretariat stood stud at Claiborne following his Triple Crown win.

Bull and Waddell Hancock (center) with their children (standing) Arthur and Clay, and (seated) Seth and Dell. (Photo courtesy of the Hancock family)

Bull Hancock had a simple answer to the question he often got about how to breed winners, says Larry Marnett, Ph.D., director of the Hancock Laboratory.

“He said, ‘you breed the best to the best and hope for the best,” Marnett says.

And that philosophy – of bringing “the best” together – has also contributed to the successes of the Hancock Laboratory.

“I’ve tried to use the resources of the Hancock Lab to catalyze multi-investigator science, to bring excellent scientists together to focus on challenging problems,” says Marnett, who has directed the lab since 1989.

This strategy of providing “seed” funding to promote multi-investigator studies became part of the philosophy of the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center when it was founded in 1993, 21 years after the Hancock Laboratory was established.

“The Hancock Lab was one of the first named laboratories in the country for cancer research,” Marnett says. “It was a very important building block for the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.”

“I think some people might even call it the cornerstone of the Cancer Center,” Dell Hancock says. “When you look at the whole thing now and realize what it’s become – it sure made mama proud – and it makes all of us proud to think that we were part of the very beginning.

“I believe great things have happened at Vanderbilt for everybody who’s been touched by cancer.”

Hancock Lab highlights

Lubomir Hnilica, Ph.D., was the first director of the Hancock Laboratory.

Hnilica’s research focused on the effects of cancer-causing chemicals on histone proteins (DNA winds around histones like thread winds around a spool).

“He was working on chromatin (the combination of DNA and proteins in the cell nucleus) – and the changes in nuclear proteins during cancer – before anybody cared about chromatin,” Marnett says. “He was way ahead of his time.”

Hnilica was killed in an automobile accident in 1986.

After Marnett joined the Vanderbilt faculty as the Mary Geddes Stahlman Chair in Cancer Research and director of the Hancock Laboratory, the focus of the lab shifted to inflammation and its role in the development of cancer.

One of the lab’s first multi-investigator efforts began with the observation in the early 1990s that people who took aspirin regularly had reduced mortality from colon cancer.

Marnett was studying the protein target of aspirin – an enzyme called cyclooxygenase (COX), which comes in multiple forms, including COX-1 and COX-2. He gathered a team of “thoroughbred” scientists at Vanderbilt to explore aspirin’s cancer-slowing action in the gastrointestinal tract. They demonstrated that COX-2 was aspirin’s target in the gut and that the COX-2 enzyme was expressed in many cancers as they develop.

“At the pre-malignant stage, most solid tumors express COX-2, and the levels of COX-2 increase as the tumors progress,” Marnett says. “COX-2 helps drive cancer progression. So it was an obvious target for cancer prevention.”

Drugs that specifically block COX-2’s action (such as Celebrex and Vioxx) were in development at the time, and they turned out to be excellent cancer preventive agents. Unfortunately, cardiovascular side effects associated with these medicines have blunted their use (Vioxx was withdrawn from the market).

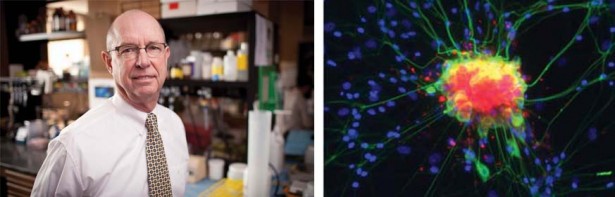

To help catch cancer early, Larry Marnett, Ph.D., director of the Hancock Laboratory, is developing imaging agents that mark cells—and, importantly, tumors—that express the enzyme COX2. (Photo by Daniel Dubois. Image at right, originally published in Nature Chemical Biology, courtesy of Marnett lab.)

In more recent studies, Marnett and his colleagues have developed a series of imaging agents targeted to COX-2. They have tethered fluorescent tracers or radioactive tracers to COX-2 specific drugs, for optical and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging.

The new agents are making it possible to “see” tumors in their earliest stages, before they turn deadly, by detecting increasing levels of COX-2.

“I think that these imaging agents may be our legacy – because the best way to treat cancer is to catch it early and get rid of it,” Marnett says.

He adds that it might even be possible to use the imaging agents – with chemotherapeutic drugs attached instead of imaging tracers – to deliver cancer-killing medicines directly to tumor cells that express COX-2.

As it moves forward into its next decade, the Hancock Laboratory will continue to follow the philosophy of bringing great people together to tackle challenging problems, Marnett says.

And the Hancock family will be there to support and celebrate along the way.

“Mama was so dedicated to the Hancock Lab and its mission, and we’re proud to continue her commitment,” Dell Hancock says. “Cancer took our father’s life at an early age, and I think the more we can do to get rid of that damn disease, the better off the world will be.

“Hopefully the Hancock Lab and Claiborne farm are both winners.”