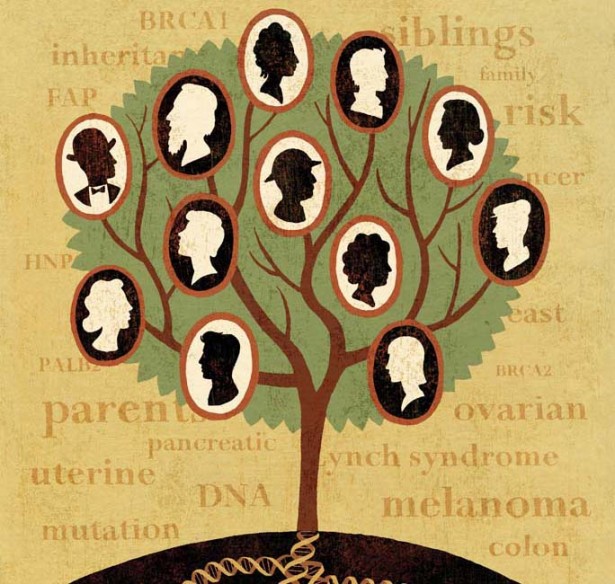

Cancer and the Family Tree

March 12, 2013 | Dagny Stuart

Illustration by James Steinberg

Family photos tell the tale of genetics, providing visual evidence of hereditary patterns in a family tree. The same features are seen again and again in the faces and bodies of successive generations, physical traits passed down from one branch to the next that help explain why a toddler looks “just like her grandmother.”

Brown eyes, red hair, a set of dimples – these hereditary features are genetic signposts, marking a child as a descendant of a specific family line.

But other inherited traits are less benign. More than 4,000 diseases, including cancer, are linked to altered genes inherited from one or both parents.

In humans, these hereditary characteristics are determined by two sets of genes – one acquired from the mother and one from the father – and whether the gene is dominant enough to cancel out another form of that gene. Inheriting a copy of the same gene from each parent, or inheriting a dominant gene from one parent, determines whether or not a descendant is likely to develop a trait – like brown eyes – or susceptibility to a disease.

Family Secrets

For decades, Patricia Fielding’s genetic inheritance was a mystery. Adopted as a toddler, she didn’t know anything about her biological parents until her mid-30s when she finally contacted and developed an ongoing relationship with her biological mother. She learned that her father had already passed away at age 32 from colon cancer.

It was years later, while she was playing with her son on the floor, that she noticed something odd.

“I felt like I was laying on top of something, like there was this rock in my belly,” she remembered.

Fielding, 54, a former IT technical assistant from Mt. Juliet, Tenn., had no idea that the “rock” in her belly was directly linked to her father’s early death – an ominous clue about her own risk of developing cancer and the risk of passing on that trait to her own children.

Patricia Fielding discovered that her ovarian cancer and her father’s early death from colon cancer were genetically linked. Photo by John Russell

A CT scan revealed a tumor on one of Fielding’s ovaries. Before doctors could operate, the tumor ruptured and the subsequent surgery revealed an aggressive clear cell carcinoma on one ovary and a slower growing cancer on the other. Her Vanderbilt physician performed a hysterectomy, removing the reproductive organs along with some lymph nodes, and Fielding underwent several rounds of chemotherapy to attack any cancer cells that might have spread into other parts of her body.

During Fielding’s cancer treatment, a genetic professional from Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center asked if she wanted to do genetic testing.

“I didn’t know until I was diagnosed with it that ovarian cancer is also hereditary and hadn’t thought about it – had no clue,” said Fielding.

Through Vanderbilt-Ingram’s Clinical and Translational Hereditary Cancer Program, Fielding received individualized counseling and genetic testing. During the consultations, patients and counselors create a family tree, filling in all of the known types of cancer and other diseases that have affected at least three generations of family members. Fielding realized that her father’s colon cancer wasn’t her only potential inherited cancer risk. There was also cancer on her mother’s side of the family.

“I had two aunts that had ovarian cancer and one of them died fairly young…in her 40s,” said Fielding.

DNA Detectives

From a simple blood sample, scientists performed a genetic test and discovered that Fielding had an inherited disease known as Lynch syndrome, a form of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) that is passed down from parent to child 50 percent of the time.

Lynch syndrome is caused by mutations in genes involved in repairing mistakes in our DNA. The presence of one of these mutations gives a person up to a 70 percent lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer. In women, Lynch syndrome increases the chance of developing endometrial (lining of the uterus) or ovarian cancer.

Fielding had one of those mutated genes.

“Even though this is a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, endometrial cancer can often be the primary cancer in the family,” explained Duveen Sturgeon, R.N., program coordinator of the Vanderbilt Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Registry.

Among women with HNPCC or Lynch syndrome, the risk of endometrial cancer rises to almost 60 percent. Individuals with Lynch Syndrome are at increased risk for cancers of the stomach, small intestine, liver, gallbladder ducts, upper urinary tract, pancreas, prostate and brain. These patients also are more likely to develop multiple cancers or have a recurrence of disease.

While Vanderbilt-Ingram’s genetic counselors are looking for obvious clues on a family tree, they are often surprised by what they don’t see among the genetic branches.

“Even in families that do not appear to have any hereditary features, when the testing is done they do carry a mismatch repair gene mutation which is diagnostic for Lynch syndrome,” said Sturgeon. “Then you have to sit down and look at the rest of the family to see who else is at risk. It’s really important to diagnose these people who have this increased risk so that physicians can do the surveillance and screening necessary to either prevent cancer from developing or catch it early.”

The genetic tests do not indicate someone actually has cancer. They simply screen for a mutation that indicates a patient has a higher likelihood of developing a specific form of cancer.

Genetic Clues

“Cancer is very common, but the true hereditary cancers – the ones where there is an actual gene or gene mutation linked to the development of cancer in a family – are really pretty rare,” explained Georgia Wiesner, M.D., professor of Medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Hereditary Cancer Program.

Inherited colorectal cancer mutations are a good example. About 160,000 new cases of colorectal cancer are diagnosed in the United States every year but only about 2 percent to 7 percent of these cancers are caused by Lynch syndrome.

“We call those ‘high-risk cancer syndromes,’ meaning if an individual has a mutation they are at very high risk for developing cancer,” said Wiesner. “The marker doesn’t say there is cancer there. The marker says they are at high risk.”

Wiesner, who has been named an Ingram Professor of Cancer Research, was recruited to Vanderbilt-Ingram to lead the new Clinical and Translational Hereditary Cancer Program that will expand and enhance the Cancer Center’s menu of hereditary cancer services for patients and physicians.

“Vanderbilt is a real leader in trying to figure out the specific genes that are causing cancer. We’re doing that at the tumor level now but I think we’ll be able to back up and look at specific markers in people that they were born with that would indicate they are at high risk,” said Wiesner.

In addition to clear-cut cancer markers like Lynch syndrome, scientists already have found specific genes linked to inherited forms of breast cancer.

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, identified in the 1990s, were among the first genes tied to a family risk of breast and ovarian cancer. In normal cells, the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes help keep the cells’ DNA stable, but when these genes are mutated the tumor suppressor function is turned off, leading to a high risk of cancer among women and men who inherit these mutations.

The mutations are more often found in families with multiple cases of breast cancer and individuals who develop both breast and ovarian cancer. Those from an Ashkenazi (Central and Eastern European) Jewish background are also at higher risk of inheriting this mutation.

According to the National Cancer Institute, women who inherit a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation are five times more likely to develop breast cancer.

Family Matters

Sara Lewis, M.S., a Licensed Certified Genetic Counselor at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Hereditary Cancer Program, counsels patients who want to know about their family cancer risk.

As she helps a patient create a family tree, Lewis is looking for patterns among the branches that may suggest a family has a hereditary predisposition to cancer. Features in a family that may raise concern include a relative with early onset cancer diagnosed before age 50, someone who had more than one type of cancer, multiple people in several generations having similar cancers or an unusual form of cancer like male breast cancer or a sarcoma.

“Based on those features we’ll spend a lot of time talking about the genetics of cancer and how those features are related to increased cancer risk over time. We’ll talk about the pros and cons of genetic testing…what the testing will tell us in terms of cancer risk and medical management considerations. We will also discuss how the genetic testing may provide information for family members and their risk of cancer development,” said Lewis.

One of the first questions patients ask is whether insurance will cover the tests. Medicare and most major health insurance companies pay for genetic testing if there is a documented family risk.

A team of genetics professionals, including Duveen Sturgeon, R.N., (left), Georgia Wiesner, M.D., (center), and Sara Lewis, M.S., (right), help patients and families determine and understand their risk of hereditary cancers. Photos by Susan Urmy

Patients are also concerned about privacy and discrimination, worrying that a positive genetic test will keep them from getting a job or keeping their health insurance. But in 2009, the federal government implemented the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), which prohibits discrimination in health coverage and employment based on genetic information.

Lewis said her patients who opt to do genetic testing have a remarkable instinct about the likelihood of finding a genetic mutation.

“Patients sometimes just know…they know if they’re going to have this risk or not. In the seven years I’ve been a counselor I’ve only had two patients who didn’t expect the results,” said Lewis.

Since Patricia Fielding knew a little about her family history, she wasn’t surprised by her positive test for Lynch syndrome.

“It didn’t devastate me. When you’re in the high risk category, you have to have more testing, more screening. I guess I will just have to be more proactive about what’s going on so if anything comes up I can catch it early,” said Fielding.

Patients who test positive for a mutation are faced with new challenges, including the need for frequent screening or even preventive surgery. Women with specific mutations like the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene sometimes choose to have their breasts or ovaries removed as a preventive measure. Those with Lynch syndrome may have their ovaries removed or undergo a hysterectomy.

Since Fielding already had her ovaries and uterus removed, her current risk from the Lynch syndrome mutation is related to colorectal cancer. She manages to laugh when she talks about her new cancer screening regimen.

“Now I get to have a colonoscopy every year and have to do the endoscope every two years. They’re no fun but there’s no alternative. I’d rather go through a colonoscopy than having to go through chemo again if I can help it.”

The decision to test or not to test can be difficult because the presence of a genetic mutation can have implications for succeeding generations. The lab results – both positive and negative – can trigger strong emotions. Guilt is at the top of the list.

Parents often express a sense of guilt for having passed on a genetic mutation to their children.

Lewis helps patients consider the genetic information in a different light.

“You couldn’t have prevented it and you also didn’t cause it,” said Lewis. “You’re providing your child a gift of information that will allow us to take care of your son or daughter and help them obtain appropriate cancer screenings at the proper time.”

Then there is survivor guilt for individuals who don’t have a targeted mutation, especially if several other family members already have cancer or are at high risk.

Vanderbilt-Ingram’s genetic counselors work with patients to put these strong emotions in perspective.

“It’s not an easy emotion to put aside but we help them reframe it so maybe they can take that pressure off of themselves,” said Lewis.

Fielding feels empowered by the knowledge of her family heritage and has encouraged her adult son and her sister to undergo genetic testing.

“It’s not something to be fearful of. Just because you have the mutated gene doesn’t mean you are going to get cancer, but it does let you know that you need to be more proactive. It gives you a place to start,” said Fielding.

While scientists have identified several genetic mutations linked to various forms of cancer, the genetic underpinnings of some hereditary cancers are still a mystery. Genetic tests may come back negative even among families with a strong history of cancer. Scientists simply may not have identified the important mutations and, in those cases, family members may still choose to get more frequent screenings.

While genes play an important role in cancer development, environmental factors may also be at play. Families with a history of smoking or a poor diet may have an increased disease risk.

Georgia Wiesner believes most cancer may be the result of a more subtle interplay of factors.

“Where cancer research is going very quickly is this dual component of heredity and our environment. That is where I believe most cancers are linked. We are all born with beneficial markers or detrimental markers and then we live our lives and are exposed to certain carcinogens. The person who has a modest susceptibility coupled with a carcinogen or a lifestyle choice may have an enhanced risk for cancer. That’s where the explanation for most cancers will be found,” Wiesner predicted.

2 Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

How we do to be tested?

Is there a phone number we can call?

Thanks

Comment by Thais Miller — April 11, 2013 @ 11:33 am

Here’s a website for the Family Cancer Risk Service with more details and contact information:

http://www.vicc.org/fcrs/

Comment by diana — June 28, 2013 @ 8:20 am