Spotlight: NEUROENDOCRINE TUMOR

Back at the Bench

Turning the tables on “unusual” tumors

June 22, 2011 | Leslie Hill

Jimmy Caldwell was looking for something to take his mind off the stress of owning a small business. He had always been handy – with 12 years of industrial maintenance work and one renovated old house under his belt – so when he read a magazine article about woodworking, he immediately purchased a lathe, set up shop in his garage and taught himself the craft.

“I started making small things like pens. I liked that they were functional but also looked nice,” he said. “It was an outlet. I could get away from my work and put my mind on something else.”

But in early 2009, the hobby was no longer providing the relief it usually did. The 48-year-old was feeling weak and short of breath and went to see his primary care physician near his home in Lexington, Tenn. Many rounds of testing uncovered the problem: a neuroendocrine tumor in Caldwell’s stomach.

No “usual” tumor

The best word to describe neuroendocrine tumors, says Eric Liu, M.D., is “unusual.”

Neuroendocrine tumors are a diverse group of tumors that can appear in almost any organ of the body, with the digestive system, pancreas and lung being the most common sites. These tumors develop in neuroendocrine cells, which release hormones to regulate many bodily functions. Typically, the cells release hormones in response to food intake and energy needs. When the cells become cancerous, the signaling goes haywire and higher amounts of hormone are released, resulting in a variety of unusual symptoms.

“They can really do some strange things,” said Liu, an assistant professor of surgery at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. “These tumors can behave very differently. Some of them are very benign and quiet and don’t bother people for a long time. Sometimes they cause unstoppable diarrhea or other strange hormonal problems – rashes, low blood sugar, ulcers, wheezing, cramps or flushing.”

Though rare (about 25 people per million), they also strike an unusually broad swath of the population.

“Frequently these tumors probably start when people are in their 20s or 30s, but they grow so quietly, for such a long time, the patient doesn’t know until they are 40 or 50,” Liu said.

Because the tumors are so slow growing, chemotherapy is usually ineffective. Some medications have been successful, but the best treatment option is to surgically remove each tumor and then closely monitor for recurrence.

Most of Caldwell’s tumor was removed during the stomach scope procedure that diagnosed the cancer, but he consulted a surgeon about removing more tissue around the tumor to be sure all the cancer was eliminated. The surgeon was optimistic that Caldwell wouldn’t need any further treatments, but ordered a CT scan to confirm.

Jimmy Caldwell knows that, despite living with cancer, his quality of life is good as long as he can spend time at his lathe, making pens and other small wood crafts. (Photo by Daniel Dubois)

“He called back two days later and told me he couldn’t do the surgery because the cancer had gone to my liver,” Caldwell recalled. “I went from the initial shock of hearing I had cancer to thinking I was going to be fine to hearing it was incurable. I had no idea what to expect at this point.”

The surgeon referred Caldwell to Jordan Berlin, M.D., Ingram Associate Professor of Cancer Research at Vanderbilt-Ingram.

“When Dr. Berlin and I talked the first time, he said he couldn’t fix it – but he could make it to where I could live with it probably for a long time. I felt much better hearing that.”

Berlin enrolled Caldwell in a research study of the medications Avastin (a drug that stops the formation of blood vessels that bring oxygen and nutrients to tumors) and Torisel (a drug that blocks a signal for cancer cells to multiply).

The combination caused terrible mouth sores and decreased appetite. When the medications were adjusted, his appetite returned but he couldn’t keep food down and began to have severe abdominal pain.

Over three weeks, he had lost 17 pounds and had to go to the ER because of severe pain after a meal.

Berlin suspected that Caldwell needed to have his gallbladder removed, and a visit to his local ER confirmed that, but the staff deemed surgery too risky because of his cancer.

Over the next month, Caldwell was constantly in and out of the hospital with severe pain and couldn’t even eat Jell-O or water.

He called Berlin and said something had to be done.

“I’m not pushy at all, not that type of person, but I was depressed, totally at the end of my rope. I was so weak and had nothing to look forward to every day except being miserable.”

Berlin contacted Liu, who was incredulous that no one would operate and scheduled the surgery for the following day.

Making the unusual routine

The problem with an unusual cancer is that there is no usual course for diagnosis and treatment. Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center is attempting to turn unusual into routine with the formation of the Vanderbilt Neuroendocrine Center.

“We’re trying to build a center where patients with these rather unusual diseases can come for comprehensive, cutting-edge care with new technologies and with collaborations with centers around the world,” Liu said.

To prepare for opening the center, Liu spent a year at Uppsala University in Uppsala, Sweden, a small city just north of Stockholm. The University began seeing neuroendocrine tumor patients in 1976 and became a Center of Excellence in 2009, drawing patients from around the world.

“The survival time for people in Uppsala is much, much better due to careful care, using lots of technology and being aggressive,” Liu said.

Investigational 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT imaging identifies several tumors spread to the liver (arrows) not visible on standard scans. These tumors – nine in all – were confirmed surgically and removed. (Image courtesy of Ronald Walker, M.D.)

“The problem in America is that physicians think the tumors are so slow-growing that the patient will be fine. They’re just left to experience these horrible symptoms. We know that these patients need our help, and my goal is to provide a place in the U.S. for them to come. We work together with other neuroendocrine specialists around the country so these patients don’t feel so lost.”

The Vanderbilt Neuroendocrine Center brings together a multi-disciplinary team with the latest diagnostic and treatment tools, and the newest tool in its arsenal is a scan called 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the affiliated VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System are the first in the nation to perform this scan to successfully locate the presence of tumors.

Most PET scans rely on a radioactive sugar to detect tumors, which doesn’t work well for neuroendocrine tumors because they are slow-growing and do not consume much sugar. However, neuroendocrine tumors have a surface receptor for the hormone somatostatin. In this new scan, a radioactive gallium atom is attached to a somatostatin-like molecule, which is attracted to the receptors on the neuroendocrine tumor. The resulting image shows exactly where neuroendocrine tumors are located in the body.

Ronald Walker, M.D., professor of Clinical Radiology and Radiological Sciences and a Cancer Center member said the new gallium scan had four times the resolution of the standard scan, a major improvement for better diagnosis and treatment.

“That makes a big difference if you’re planning treatment, either surgery or just deciding if someone is a surgical candidate. You really need to know how far the tumor has spread,” he said.

The gallium scan also opens up an exciting new treatment modality called radiopeptide therapy. Instead of using a signaling molecule to indicate where the tumor is located, a radiation molecule is used. The radiation is delivered directly to the tumor, which kills it.

“If you perform the scan and see tumors light up, then you know that radiation therapy hooked to the same molecule would also home in on the tumor,” Walker said.

Last fall, Vanderbilt-Ingram received two single-use exemptions from the Food and Drug Administration to perform the first scans on Wendy Marber, a 60-year-old retired teacher living in Boston. (Recently, the FDA granted Vanderbilt approval to use the compound routinely in research studies – the first such approval in the nation.)

Marber was first diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2006, and then neuroendocrine tumors of the liver in 2008, and was receiving treatment at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Mount Sinai Medical Center.

When her neuroendocrine cancer recurred in early 2010 and surgery was deemed necessary, her providers suggested she either travel to Switzerland or Vanderbilt for a gallium scan to determine the location of the tumors. The choice to stay in the country was an easy one, especially after consulting with Liu.

“We knew of Vanderbilt and its reputation and had a phone call with Eric and really liked him. He probably spent an hour and a half over two calls on the phone. It was obvious he cared about this cancer and the quality of the diagnostic process,” Marber said.

Eight small tumors showed up on the gallium scan, and Marber said the higher accuracy of the scan made her more confident that the surgeons at Mount Sinai would be able to find and remove all of them.

Liu said this collaboration between medical centers will be a hallmark of Vanderbilt’s Neuroendocrine Center.

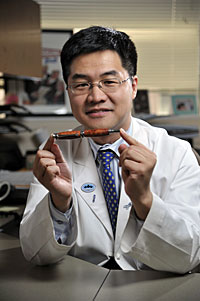

Eric Liu, M.D., proudly holds a hand-crafted wooden pen made by Caldwell. (Photo by John Russell)

“We want to be a referral center for referral centers. We’re bringing all the tools together in one place so patients don’t have to fly across the world for their care.

Back in the shop

One month after Liu performed surgery to remove Caldwell’s gallbladder, Caldwell had put on 25 pounds and felt back to his normal self.

“It was just a helpless feeling that everyone knows what is wrong with me but says they won’t fix me,” he said. “What was just a simple operation to Dr. Liu meant everything to me.”

Caldwell is now taking Sutent three times a day for treatment, but his last scan showed that his tumors were stable. He showed his appreciation by giving Liu an intricately carved wooden ink pen he made in his garage woodshop.

Caldwell knows that despite living with cancer he has good quality of life because he can spend time at his lathe.

And Liu has the pen to prove it.

***

Editor’s note: Jimmy Caldwell died Sunday, June 5, 2011 at his home in Lexington, Tenn., at age 49. The family requests memorials be made to the First Baptist Church, Kirkland Center, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Unity Hospice or the charity of the donors choice.

***

Read about how diagnosis with this rare tumor helped forge a friendship and create a legacy of giving in “Friendships, Legacies.”

2 Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Jimmy just passed away and was the finest man I have ever known. I never heard anything negative come out of his mouth and I never seen him frown. He was a Christian, a devoted family man, and a friend to every person he met. Rest in peace buddy.

Comment by Mack — July 8, 2011 @ 8:55 am

Mack, thank you so much for your kind words. We at VICC found about about Jimmy’s passing day before yesterday, and we’re so very sorry for your community’s loss.

Comment by Heather Burchfield — July 8, 2011 @ 9:22 am